According to a recent Health and Social Care Information Centre report, we are seeing a return of diseases common in the Victorian era.

The report highlights five conditions: gout, tuberculosis, measles, malnutrition and whooping cough. It has a longer listing of rarer conditions, which also conjure the image of bygone pestilence and depravity – scurvy, mumps, rickets, scarlet fever, cholera, diphtheria and typhoid.

In a time of global public health disasters of biblical proportions, in west Africa and the Middle East, it appears an indulgence perhaps to be concerned about these conditions. We may be tempted to dismiss the report as a novelty. But that would be wrong: a civilized nation with an advanced economy and health system should see some conditions as markers for the failure of its public health policies or services. But which markers?

The NHS has "never events" as quality of care markers. Never events are serious, largely preventable patient safety incidents. They include wrong site surgery, wrong route chemotherapy administration and suicide during psychiatric admission. The time has perhaps come for us to develop never events in public health.

In the HSCIC report, gout is the strongest contender for a returning Victorian disease – it may well be linked to an ageing population, epidemic obesity and excess alcohol consumption; 70% of cases are in the over 60s. There were 86,870 hospital admissions where gout was coded, an increase of 78% on the same period in 2009-10 (48,720). There were 13.5 gout admissions per 100,000 population in the 10% most deprived areas, 8.3 gout admissions per 100,000 population in the 10% least deprived areas, in 2013-14. Formerly the disease of kings, gout is now very clearly associated with deprivation.

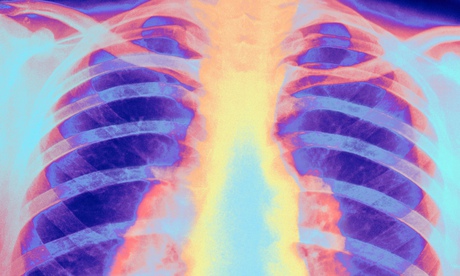

Tuberculosis and rickets are the strongest markers of both Victorian disease and public health never events. We should certainly regard tuberculosis contracted in this country, and tuberculosis deaths, as never events. The HSCIC figures show a welcome decline in hospital admissions for tuberculosis. New notifications are also stabilising but at an unacceptably high level, with 8,751 cases reported in 2012, an incidence of 13.9 per 100,000 population. The need to spend time in hospital should be declining as services become better able to treat people at home and cases are hopefully identified earlier and at less infectious stages.

Hospital admissions with a scarlet fever coding doubled, from 403 to 845. Public policy measures to prevent this, and the clinical significance of this change are difficult to determine; historically scarlet fever is a disease of deprivation, tamed by antibiotics. It manifests long cyclical rises and falls over 40 years – the rise may be part of that cycle. But we should be concerned we are seeing a period of enforced deprivation, with the biggest cut in average wages since Dickens' era.

Measles and whooping cough were rampant in Victorian times but remained so until the 1990s – hardly Victorian, but they should be never events as they are completely preventable through immunisation.

Over the past five years there was a 71% increase in hospital admissions where malnutrition was coded, from 3,900 admissions in 2009-10 to 6,690 admissions in 2013-14. Patients are being found to be malnourished on admission to hospital as a result of neglect, in care homes, or at home. The figures may also reflect more complete coding and better awareness of nutrition issues in hospitals.

Rickets is a concern – a lack of vitamin D due to dietary and sunlight deficiency. We may have contributed to this through campaigns to keep people out of the sun. It is more common in dark skinned people, but also in deprived communities, black and white. We could reverse our skin cancer campaigns and encourage little and often sun exposure, or we could correct it by fortifying milk with vitamin D. Scurvy is rare – 72 cases in 2009-10, rising to 94 cases last year, but vitamin C deficiency really must be a marker of failed public health nutrition.

Interpreting the figures, we should be a little cautious about the impact of hospital coding – there has been upward pressure to code everything in the patient's discharge summary for hospitals to pull in maximum payment by results.

The figures do reflect classical diseases associated with mass poverty of Victorian times and so they should be a barometer for us. Gout, malnutrition, scurvy and rickets point us to failures in the nation's diet. Our complacent notion that we have better diets must be thrown out and there must be a national drive for a healthy, nutritious and balanced diet, casting aside the interests of the food industry. Major vaccine-preventable infectious diseases should be prevented.

We should be concerned about these figures – they tell us of a picture of neglect – by government with its active impoverishment of poorer parts of our society and with its complacent neglect of public health nutrition. And neglect too by the health and care system in respect of malnutrition, dehydration, failure to vaccinate and neglect of nutrition.

John Middleton is vice president for policy at the UK Faculty of Public Health

This article is part of the Beveridge Revisited series from Guardian Society Professionals, revising Sir William Beveridge's five great social evils for the 21st century.

Are you a member of our online community? Join the Healthcare Professionals Network to receive regular emails and exclusive offers.

This article was amended on 11 August to include some additional statistics on gout.