A hospital doctor has been acquitted of carrying out female genital mutilation (FGM) on a patient, in the first prosecution since the practice was outlawed in England and Wales 29 years ago.

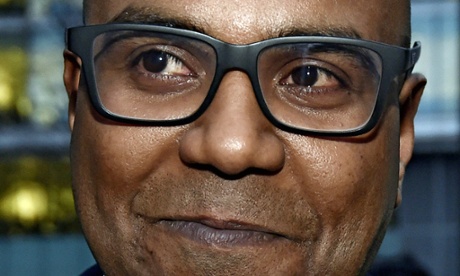

A jury took less than 30 minutes to find Dr Dhanuson Dharmasena, 32, not guilty of subjecting a mother to FGM after he delivered her baby. A second man, Hasan Mohamed, 41, was also found not guilty of aiding and abetting the doctor.

Dharmasena was charged with committing FGM by stitching up the mother following the birth of her first child at the Whittington hospital in London in November 2012. He said he had sutured her with a single stitch to stop her bleeding from an incision required for childbirth, because she had previously been subjected to FGM in her native Somalia.

Mr Justice Sweeney told the jury on Wednesday everyone agreed Dharmasena had saved the life of the woman’s baby during an emergency delivery.

In summing up, he said: “It is no doubt in this case that Dr Dharmasena had been badly let down by a number of systematic failures which were no fault of his own at the Whittington hospital,” the judge said. He added that the woman had been let down by the hospital, which should have picked up her condition as someone who had suffered FGM much earlier.

In a statement Dharmasena said: “I am extremely relieved with the court’s verdict and I am grateful to the jury for their careful consideration of the facts. I have always maintained that FGM is an abhorrent practice that has no medical justification; however I cannot comment further on the details of this case due to patient confidentiality.

“I would like to thank my family, friends, legal team and all those who supported me through this difficult time and I look forward to putting this matter behind me.”

The charge against Dharmasena was announced in March 2014 in a high-profile statement by the director of public prosecutions, Alison Saunders, following political and media pressure on the police and Crown Prosecution Service at the failure to prosecute anyone for the offence since FGM was outlawed in the UK in 1985.

But Saunders said the decision to bring the case to trial was still correct, noting that the judge had on three separate occasions declined to dismiss applications by the defence to halt the case.

She said that the Crown Prosecution Service should not “shy away from difficult cases” and added that the not guilty verdicts would not “affect our resolve to bring those who do commit FGM to justice where we have the evidence to do so.

“The evidence in this case meant a prosecution should be brought so that a jury could be allowed to consider the facts. We respect the decision of the jury.’’

Dharmasena has been suspended from the medical register since he was charged. He has faced death threats since the public announcement of the prosecution, and still faces an investigation by the General Medical Council and possible disciplinary action.

He told the court he had been given no training on FGM, either as a medical student or a postgraduate, or in his supervised training as a junior registrar at the Whittington. He said he had acted at all times in the woman’s best interests.

The doctor has been supported by leading obstetricians, including Prof Sarah Creighton, consultant in obstetrics and gynaecology at University College hospital.

Southwark crown court heard that the woman, now 26, who cannot be named, had undergone type 3 FGM – in which part of the labia are sewn together – as a child in Africa, and during labour the doctor had made two cuts to her vaginal opening to ensure the safe delivery of her baby.

When Dharmasena sewed her up, a midwife warned him that what he had done was illegal. The doctor disputed this. But he was concerned about what he had done and asked a consultant on duty for advice, and the more senior doctor said it would be “painful and humiliating” to remove the stitch he had made, and told him to leave it in place.

The woman at the centre of the case did not support the prosecution case. She refused to give a statement to the Metropolitan police, and told the court as far as she was concerned the doctor had delivered her baby. He told me: “You’ve won, the baby’s born and now I’m going to do some stitches.’”

Both men denied the charges against them. Dharmasena was charged under the 2003 Female Genital Mutilation Act – the first individual to be charged with an FGM offence. Mohamed was charged with aiding and abetting him.

The doctor, who qualified in 2005, and began specialising in obstetrics and gynaecology in 2008, had been at the Whittington for a month as a junior registrar in obstetrics and gynaecology, when the events took place in 2012.

Under the 2003 FGM Act, a doctor is exempted from prosecution if his actions involve a surgical operation on a woman in any stage of labour, or immediately after birth, for purposes connected with the labour or birth. Dharmasena told the jury he had acted, using a figure of eight suture, to stem bleeding from the incision. But the crown tried to claim that he had intended to close the woman up and had reinstituted her FGM, something that was not medically necessary, and a criminal offence.

The Whittington said in a statement they welcomed the verdict and that there was a “considerable amount to learn from AB’s experience” at the hospital.

“This was a unique, sensitive and complex case and, as was made clear in the trial, Dr Dharmasena is a well respected doctor and never had any intention of doing harm. We endeavour to support our clinical staff who often face difficult, challenging and emergency situations and strive to do their very best for patients.

“We are committed to providing the very best care and support for girls and women living with the consequences of FGM. We have our own specialist FGM service with staff who have experience in dealing with FGM and providing support to women.”