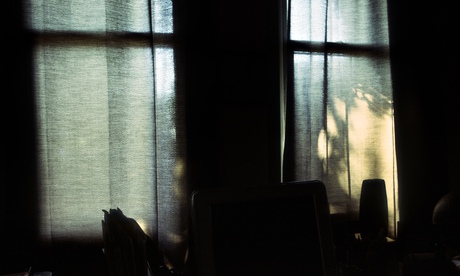

It is, writes Anna Lyndsey at the beginning of her memoir, “extraordinarily difficult to black out a room”. The light does its best to find a way in. She had blackout blinds and curtains, and layer upon layer of kitchen foil taped to the windows of the small house in Hampshire she shares with her husband. “What I mainly remember,” she says, “was how difficult it was to do. The foil kept splitting and falling off and tearing, so it was really frustrating. It was a weird combination of DIY frustration and slightly more depressing feelings. As I was doing it, I was thinking: ‘Will I see the outside world again? Will I ever come out of here? What will happen to me?’ But I didn’t have any alternative, it wasn’t a choice, it was: ‘I have got to do this because I am in agony.’ ”

The room became a kind of prison cell, but also a place of refuge. It was summer 2006. The previous year, Lyndsey, then in her early 30s, had been living in London and was working as a civil servant when she noticed her face had started to burn whenever she sat in front of her computer screen. Soon she started reacting to fluorescent lights, then sunlight. She was diagnosed with photosensitivity – an extreme and debilitating allergy to light – and had to leave her job. She moved to Hampshire to live with her partner Pete and, for a while, studied to become a piano teacher, which meant she wouldn’t have to work in an office environment.

“What happened after that, in the early summer of 2006, was the real catastrophe,” she says. Her body started reacting to light, even through multiple layers of clothing. “I learned that walls were what I had to wear,” she writes in the book, for which she has used a pseudonym. An unnecessary question: how did it make her feel? “Absolutely desperate,” she says, in a quiet voice on the phone.

Unable to leave the house, sometimes even the blacked-out room, she realised that travelling to London to see her consultant was unthinkable; she still hasn’t seen a specialist – they won’t make a house call and nobody seems to know what to do with her anyway. Most cases of photosensitivity are caused by another condition, such as lupus, or reactions to medication, but Lyndsey was told about 10% have no known cause. Her consultant tells her in correspondence that the cause is unknown, particularly for such an extreme, rare case. (Later, when she seeks alternative therapies, a “healer” suggests it’s psychological. “I prove irresistible to those of a new agey turn of mind … to cut oneself off from society, to insist on living in the dark in a sealed-up room – it is almost too perfect.”)

Her friends and family looked online to try and find anything about her extreme level of light sensitivity, and found one scientific paper that described a case like Lyndsey’s – someone who had their own blacked-out room to provide shelter from light.

Talking to people on the phone helped fill days spent in the dark – some are from her old life, but some are new people she has made contact with, many with chronic health conditions. She can watch TV during brief periods out of her blacked-out room by looking at its reflection in a mirror, but using a computer is impossible. She made up wordgames to keep herself occupied, but mainly she got through audiobook after audiobook. She couldn’t listen to music. “It stirred too many memories and too many emotions. I had loved all sorts of music, but I just couldn’t do it in the dark.”

Lyndsey had been with her husband (then boyfriend) for two years before her condition started. She writes with heartbreaking honesty about how his life has been affected, too. “I regularly felt, and still feel, racked with guilt about the whole thing and not sure if I really ought to be making the effort to leave,” she says. “I’ve also spent lots of time being terrified that he’s going to get fed up with me and decide to leave. But I suppose I try to not think about it. Also, we’ve kind of developed ways of coping with it. I’ve discovered that you can peel an awful lot of stuff away, but if you’ve got two personalities that still make each other laugh, still complement each other, even when they’re two voices in the darkness, amazingly it can keep going. There have been enough hopeful patches over the last two years that even when I’ve had bad patches, he’s very good at saying ‘Don’t give up, things have got better in the past and can get better again.’ ”

She started writing the book during a particularly bad period, cooped up in her dark room over the hot summer months of 2010. “It’s amazing what being completely bored can make you do,” she says, with a small laugh. “There are only so many talking books and Radio 4 programmes you can listen to. I was desperate to find something else I could do in the dark. I did try knitting, but it wasn’t completely successful.”

She didn’t think writing would work, because she wouldn’t be able to see what she’d written (using pencil and paper) as she went along. Instead, that proved disinhibiting – she was able to just get it out, without agonising over it. The result is extraordinary, and beautifully written.

It wasn’t particularly cathartic, and wasn’t intended to be, she says. Instead, it was a distraction that became addictive. “A project,” she says. Trying to relay what had happened to her and how it felt “just became a really interesting challenge, of the kind I used to have at work and didn’t have any more. Once I started doing it, it crowded out other, more upsetting, thoughts.”

She writes, devastatingly, about contemplating suicide. How does she manage those times? She is quiet for a while. Now that she has gone through the cycle a few times – of having to retreat to her blacked-out room for months, then periods of being able to spend more time downstairs, sometimes with the curtains open – she says, “It’s trying to remember the better times. And also you learn not to think about certain triggers. I try not to think about the future, or the things I can’t control.”

She misses the long hikes she used to go on, but now she focuses on small achievements. She has a light meter, and being able to tolerate stronger light for longer is immensely cheering. “Just these small steps back to being a bit more independent is very exciting.”

Going out into her garden for the first time “was amazing. Just being able to move freely. You don’t realise when you’re in the house all the time how cramped and restricted your walking is. It’s like when you’re in a museum and you get museum legs because you’re just shuffling along, not striding out. And the smell of everything; when I first went outside, it overwhelmed me. When I started being able to go outside with little bits of light as well, it sounds corny, but I found the beauty of nature completely overwhelming. I would stand there, looking at a tree, looking at the shape of the branches. Or I’d look at a spider and the shape of its legs. It was an intense experience.”

Lyndsey discovered she could go out for a walk at dawn and dusk for about an hour without it affecting her skin, and her husband made a canopy of black felt for the back of the car so they can drive somewhere else, such as a forest, during daylight hours, ready for a sunset walk.

She says she is feeling quite optimistic at the moment. “Because this condition is such an unknown quantity, nobody has told me that it can’t be cured, although nobody has told me that it can be – or not necessarily cured, but the mental state I’ve got into, every incremental improvement is exciting and just looking forward to them is enough, really.”

She doesn’t have much patience for people who say they can’t believe how she copes but still, I say, she sounds amazing. “I don’t think so,” she says. “I think everybody has more reserves in them than they think they have.” But she concedes this has surprised her. “If I look back, I think: ‘My God, I went through all that and I’m still sane.’ I suppose from talking to other people I know with chronic illnesses, people are just more resilient than we think we are, and we can cope with apparently impossible situations.”

• To buy Girl in the Dark by Anna Lyndsey for £13.59 (RRP £16.99) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.