The new generation of drugs hailed as a once-in-a-generation advance in treatment for cancer patients is also viewed as good news for the pharmaceutical industry – just when analysts had started to voice concerns that the pipeline of blockbuster treatments in development was starting to run dry.

Immunotherapy treatments, which use the body’s immune system to attack cancerous cells, could be as revolutionary as the arrival of chemotherapy was in the 1940s – and big pharma companies have been scrambling to get into a market that experts think could eventually be worth up to £26bn a year in sales.

“It is a really significant breakthrough” said Colin White, lead analyst for oncology at the research group Datamonitor Healthcare. “It is being seen as the third major breakthrough in cancer treatments: the first being chemotherapy, the second being targeted treatments and the third being immunotherapy.”

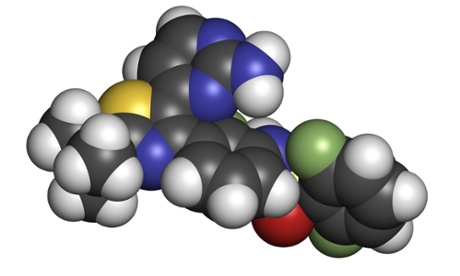

Scientists at the American Society for Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting in Chicago last weekend announced “spectacular” results from one clinical trial of patients with skin cancer. More than half the patients with advanced melanoma, many considered to have little time left, saw tumours shrink or brought under control using a combination of drugs – ipilimumab, known under the brand name Yervoy, and the as-yet unlicensed nivolumab, branded as Opdivo.

Since the start of 2014, there have been at least 44 corporate deals in the immuno-oncology market, according to Datamonitor, which tracks such transactions. One of the biggest was Pfizer’s $2.9bn collaboration with the French biotech company Cellectis.

On the rebound from its failed bid to buy AstraZeneca, Pfizer acquired a 10% stake in Cellectis and bought exclusive rights to develop immunotherapy drugs to fight 15 cancer targets. The American drugs multinational is rumoured to be interested in buying Cellectis outright, although both sides have so far declined to comment.

Another deal that got analysts excited was Bristol-Myers Squibb handing over $1.25bn to buy California-based Flexus in February - a company that was less than 18 months old and has no drugs being trialled. But Bristol-Myers Squibb already has a headstart in the immunotherapy race: its Yervoy and Opdivo brands are the two drugs that caused such a storm in Chicago last weekend.

Apart from Bristol-Myers, Merck is the only other company to have had an immunotherapy drug approved for the treatment of skin cancer. But Pfizer, Roche and a host of smaller biotech firms are racing to develop the therapies, which may work on a much broader range of cancers than previously thought.

When the UK drugs multinational AstraZeneca was fighting off the unwanted £63bn takeover attempt by Pfizer last year it warned that the cost-cutting likely to follow a takeover could delay the development of key drugs and cost lives. One of the key treatments Astra pointed to was in its immuno-oncology portfolio – a human monoclonal antibody known as MEDI4736.

One of the City’s top pharmaceuticals analysts described MEDI4736 as “the great white hope” of cancer treatments, while AstraZeneca’s head drug developer, Briggs Morrison, said it could “redefine cancer treatment” and rake in annual sales of £3.9bn.

Last year, Roche entered into a $1bn agreement with NewLink Genetics, the Iowa-based maker of the experimental Ebola vaccine, to develop immunotherapy treatments. The companies are developing an inhibitor (NLG919) designed to disrupt the mechanism by which tumours evade the patient’s immune system. NewLink has already tested similar products in patients with breast and prostate cancer.

In another sign of the booming market, companies are increasingly keen to keep their top scientific experts. Last week Bristol-Myers Squibb started legal proceedings against one of its key immunotherapy experts for allegedly violating confidentiality agreements. David Berman, a vice-president at BMS who has spent the last decade working on immunotherapy drugs, including Yervoy and Opdivo, has quit to join AstraZeneca and BMS has asked a Delaware court to stop Berman from joining AstraZeneca for a year and prevent him from ever using confidential information gained at BMS.

But the biggest question for healthcare executives interested in buying these treatments comes back to cost.

“These drugs cost too much,” Leonard Saltz, chief of gastrointestinal oncology at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, told delegates in Chicago in a widely discussed presentation reported by the Wall Street Journal.

He is concerned about the cost of the melanoma treatment developed by BMS. The combination of Yervoy and Opdivo would help patients live for almost a year without their disease getting worse, something “truly remarkable for a disease that five years ago we thought was virtually untreatable”, he said. But the drugs would cost $295,000 a patient – an “unsustainable” sum, he said.

“Cancer-drug prices are not related to the value of the drug ... Prices are based on what has come before and what the seller believes the market will bear.”