What’s it like to have a pain that just won’t go away? Complex regional pain syndrome, or CRPS, causes exactly that, and it’s as hard to diagnose as it is to understand. It can strike at any age, affects both men and women – and may be more common than previously thought.

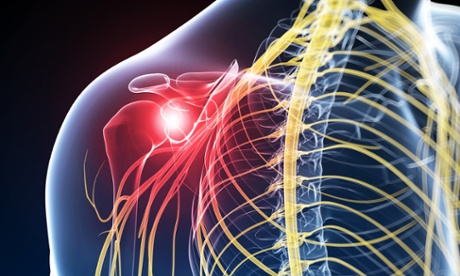

But with no specific tests to diagnose CRPS, doctors just have to look out for patients with an intense burning pain that goes beyond what would be expected from their injury – anything from a fracture to a stroke. What’s causing the pain isn’t this “triggering” injury any more – it’s the complex communication system between nerves and the brain, which means that even after an injury has healed, the pain persists.

Clare Strickland is 47 and knows first hand the debilitating effect that CRPS can have. She lives in Kent and 15 years ago she slipped down two steps and broke the big toe on her right foot. “Before that, I was just a normal single mum,” she says. “I worked part-time, went swimming three times a week, did the school run, the usual stuff. But that one slip – it changed everything.”

After three days, her toe was blue, mottled and cold, so she went back to her GP. She was diagnosed with reflex sympathetic dystrophy (now known as CRPS Type 1) and sent to a pain clinic. “It was encouraging that it was picked up early, because CRPS is rare. However, from that point onwards, I became a guinea pig, as nobody really seemed to know what to do about it.”

Strickland was in constant, searing pain. During the next four years, she tried a variety of treatments, including nerve block injections to the spine. None had any effect. The mottled-colour skin, a symptom of CRPS caused by its effect on the circulatory system, had crept up to her knee, and she couldn’t wear shoes or socks or even tolerate bedclothes touching the area. “I remember one winter going outside on my crutches in the snow with a bare foot – that’s how unbearable it would have been to let anything touch my skin.”

Taking about 30 painkiller tablets a day, Strickland felt she was “just existing”. The drugs helped, but gave her constipation, sickness – even nosebleeds and the shakes. “I had to choose between these symptoms and the pain. And the limb itself didn’t feel like my own. It didn’t even look like mine: it grew thicker hair, and longer, whiter nails – all symptoms of CRPS. I became virtually housebound, and friends drifted away.”

Dr Simon Thomson, a consultant specialising in pain medicine at Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals in Essex, explains that CRPS patients can often become so desperate that they actually ask to have the affected limb amputated. Last year, Mark Goddard, a Devon man who was injured in a motorcycle accident 17 years ago, was driven to cut his own hand off using a homemade guillotine, because his doctors refused to amputate. “It’s something we obviously don’t encourage,” says Thomson. “But CRPS, in its worst form, can cause untold handicap and misery

“It’s more common than we may have previously thought, but there’s no epidemic – just tighter diagnostic criteria. What’s frustrating is that we just don’t know what causes it. So far no genetic predisposition has been found. All we know is that it is seen more often in people who have experienced their ‘trigger’ injury at a time of psychological distress.”

Anthony Chuter, of the charity Pain UK, says the stigma of chronic pain is similar to that of mental health. “People don’t understand it: they can’t get their heads around it. A recent survey found that only 30% of people in Britain actually understand what chronic pain really is. I suffer from chronic pain, and something I get asked a lot is: ‘Aren’t you over that yet?’ The problem with all types of chronic pain, including CRPS, is that it’s 24/7, and it stops you living. It’s that simple – it doesn’t kill you, but it takes away your life.

“We want those who work in health and social care to take chronic pain more seriously. GPs are good at handing out painkillers, but people get stuck in the system as they are passed from pillar to post. You don’t hear, ‘I can’t find anything wrong with you’, any more, but you get, ‘I can’t find anything I can help you with’, instead. You start losing hope – depression goes hand in hand with chronic pain, and it’s easy to see why.”

In 2005, Strickland had a spinal cord stimulation (SCS) device implanted to target her pain, and when this stopped working in 2011, Dr Thomson recommended a Spinal Modulation Axium Neurostimulator System. This device gives targeted stimulation to a neural structure that branches off the spinal cord, called the Dorsal Root Ganglion – and is a treatment offered by a number of specialist pain clinics across the country.

According to Dr Thomson, the vast majority of cases settle down quickly. “But we need a bit more pace injected into the process – early detection is so important with CRPS. Then we use a multi-disciplinary approach: pain relief, physiotherapy, education and then, in some cases, implants like the one that Clare has.”

Strickland now only takes 20 tablets a day. “That sounds like a lot,” she says, “but the implant has changed my life. It’s the difference between taking a mouthful of pills and waiting for them to work and being in control of the pain. I can walk unaided again – and even wear both shoes. The limb will become less sensitive the more I use it, so things will hopefully get easier as time goes on. I feel like I was in prison, and now I’ve been released.”

Pain UK is an alliance of charities providing support, healthcare advice and resources for those living with pain.