In May 2011, my wife and I discovered that our first child had a cleft lip and palate. The diagnosis took place in the 22nd week of pregnancy. Unsurprisingly, the news came as a considerable shock, made worse by the fact that, just a few months earlier, we’d been forced to terminate another pregnancy at 18 weeks after the foetus was discovered to have a rare and fatal disorder that meant crucial internal organs would never develop. This new diagnosis – which turned out to be unrelated to what had gone wrong previously – caught us wholly unawares. In common with most people, we knew little about clefts. Despite being the most common birth defect, with an incidence of roughly 1 in 700 in the UK, clefts are, particularly in developed countries, seldom discussed and largely invisible. Before hearing the sonographer’s verdict that day, I’d never knowingly met or even seen anyone who had one. I vaguely knew that “hare lips” were associated with inbreeding – and, by extension, were common in remote rural communities – and I’d read JM Coetzee’s Life & Times of Michael K, whose protagonist has a cleft. But that was about the extent of my knowledge.

Learning that your child has a disability, no matter how mild (and as birth defects go, clefts are mild), is a shock on several levels. There’s the selfish impulse to ask: “Why me?” (In our case, this was magnified by a further question: “Why us, again?”) Equally selfishly, there’s the fear of what it will entail, the worry and disruption that it may cause. Pretty much every parent, I think, starts from the assumption that his or her child will be normal (whatever that really means). This assumption is so deeply embedded that any certain knowledge of abnormality represents a serious blow. You instantly feel as if you are crossing a threshold, being drawn into another, unwelcome kind of existence. How will you cope, you find yourself asking, with having a child who isn’t the flawless being you not only expected but, in some sense, considered your right? And how, no less importantly, will other people’s reactions affect you?

Yet at the same time, I felt something more hopeful stir within me that afternoon: an intense stab of sympathy for the child growing inside my wife, Gudrun, who I knew would face more obstacles than other children. How might this affect him? (We’d learned by now that our child almost certainly was a “he”.) Would it blight his life, or make him a stronger, better person? Such questions were, I suppose, the first intimations of love.

Because our son’s cleft was picked up at 22 weeks, we were told right away that we could still have an abortion. (The legal limit for abortions is 24 weeks; beyond that, they are permitted for “severe” disabilities such as Down’s syndrome but not for mild ones such as a cleft or club foot.) Our immediate instinct was that we shouldn’t. The doctors we spoke to that afternoon, while stressing that the choice was ours to make, were broadly positive about our son’s prospects. They said that surgery for clefts had come on a great deal in recent decades, and would continue to improve. Although clefts had, in the past, often been a genuine blight right up into adulthood, nowadays they were in most cases eminently fixable. Ultimately, it was likely that our son would lead a “normal” life.

So, to begin with, that was our position. In the meantime, we tried to combat our ignorance. We scoured the internet and read up about clefts. We looked at pictures, both of babies with untreated lips and older children who’d had them repaired. We learned some basic but important facts. Clefts form very early during pregnancy, typically around five to seven weeks, when the face, which starts out in separate sections, knits itself together. It does so along seams; a cleft occurs when something goes wrong with the knitting process, and the cells don’t bond as they should. The causes are largely mysterious. There’s a genetic component: to a degree, clefts run in families (not that Gudrun or I knew of any histories in ours), and if a couple has a baby with a cleft, the odds are significantly raised for subsequent pregnancies. But clefts aren’t simply the work of genes; environment plays a part in helping the genes “express” themselves. Here, though, the causation is even less well understood: precisely which environmental factors may “trigger” a cleft has never been satisfactorily established.

Clefts occur in two main places: externally, on the upper lip (sometimes extending up into the nose), and inside the mouth, on the upper gum and palate. Sometimes just the lip is involved, sometimes just the palate, although a cleft in both places – as was the case for our son – is the most common presentation. Clefts can be a symptom of a more serious condition – for instance, babies born with Edwards and Patau syndromes usually have clefts – but in the majority of cases they are an isolated defect. The baby will be healthy in every other respect.

During this period, a family friend put me in touch with a woman whose 16-year-old daughter had been born with a cleft through both her lip and palate. We spoke on the phone, and the woman told me that her daughter had had 13 operations, including one, in her early teens, that involved breaking and then realigning her jaw. She said that the treatments had been a “long haul”, but that they’d served to make her daughter more precious to her.

A few days later, we returned to the prenatal unit to talk to the doctors again. This time, we were taken to meet a senior doctor, an expert in the field of prenatal scanning. He carried an obvious authority with his colleagues and had a gruff, “no bullshit” manner. We spent 15 minutes or so in his company, and left the room feeling considerably less sure of ourselves.

“Of course, you can go and see the cleft nurse,” he began, “and she will show you pretty before and after pictures and tell you that everything will be OK. But let me tell you what it’s really like.” He launched into a litany of potential problems. There would be endless operations, the likelihood of ostracisation, bullying, low self-esteem. The shape of the face could be affected, with the entire upper jaw recessed. Breastfeeding would be impossible, since the gap in our son’s palate meant that he wouldn’t be able to suck. Later, there would be problems with food coming out of the nose. “It will be disgusting,” the doctor said, and used his hands to mimic the motion of food exiting the nose. “Your son may speak with a funny voice, a biiit liiiiike thiiiis” – and here he did a pantomime impression of someone with a severe speech defect, all hyper-nasality and elongated vowels. “You are both attractive people,” he concluded. “You could start again. You need to go away, drink a bottle of wine and think about this very, very carefully.”

Afterwards, reeling from his bluntness, we headed outside the hospital’s main entrance for some fresh air. A few minutes later, the doctor came out. As he walked past us, he stopped. “There’s one more thing,” he said. “People who have clefts, when they have children and it’s discovered that their children have clefts, in most cases, they decide not to go ahead with the pregnancy.” As he made his way to his car, this final sally hung in the air. There seemed little doubt as to what he thought.

I’m afraid that we very nearly did change our minds. Inevitably, our meeting with the senior doctor greatly influenced us. Parenthood, at the best of times, is a leap into the unknown. When you discover that your child has a defect, the sense of being in the dark only intensifies. No matter how much you read up about the condition, learn about the operations, the probable side-effects and so on, the reality of being a parent in such circumstances remains opaque, unimaginable. At the same time, and adding to our sense of confusion, we found genuinely useful guidance hard to come by. Because parents have the right to abort a child up to 24 weeks, the medical profession, we found, adopts a stance of neutrality: we were told many times that whatever decision we made “would be the right one”, which didn’t actually make deciding easier. Friends and family, while supportive, broadly took a similar view: the decision was ours to make; no one envied us. And so, at first, we set great store by what the doctor said. Here at last, it seemed, was someone willing to cut through the bland circumlocutions and communicate what no one else was brave enough to spell out.

But our trust in him, I came to realise, was misplaced. The fact that he was an expert in prenatal scanning didn’t mean that he had a better idea than we did about what being the parent of a child with a cleft actually involved. He knew about the potential problems – but had no sense of the reality. Perhaps his outlook was connected to his background, his experience. Had a lifetime in foetal scanning, searching for defects, made him unusually intolerant of imperfection?

In the end, two things returned us to our initial position. First, and most important, was Gudrun’s understandable distress at the idea of aborting another wanted child, especially, once again, at such a late stage. A termination at 18 or 22 weeks is a very different matter to one at six or eight weeks. She simply didn’t think she could go through with it – especially when, unlike last time, we did have a choice.

Second, we received some advice – via email – from another doctor, the surgeon father of a colleague of mine. An abortion, he wrote, seemed an “extreme measure” and would be a “very sad outcome”. The large majority of clefts really weren’t that big a problem. And he worried about the “psychological damage” a termination might inflict on my wife. I was deeply affected by his words, so different in tone from those of the senior doctor. Instead of focusing on the potential negatives of our child’s condition, his main concern was the effect an abortion would have – the regret it might occasion, the happiness and fulfilment it might cause us to miss out on. He was writing, it seemed to me, more in love than in fear. And his email made me realise that the senior doctor didn’t have a monopoly on honesty. After all, this doctor had no reason to sugar-coat his advice.

We probably would have had the baby anyway, as by this point Gudrun had more or less made up her mind. But the surgeon’s email certainly helped make me confident about our decision. I realised that I should have trusted my initial instincts on the afternoon of the diagnosis, when I’d felt such empathy for my unborn son. If he wasn’t quite perfect, quite “normal”, then so be it. Whatever his defect was, we should embrace it, cherish it, not take the easy course of rubbing it out.

Knowing in advance that your child has a defect inevitably complicates your feelings about the birth. For mothers, I think, this is especially true. Normally, women coping with the myriad discomforts of late-term pregnancy, not to mention anxieties about labour, will at least be able to look forward to the moment, post-delivery, when they finally take their baby in their arms and luxuriate in his or her unblemished perfection. Gudrun was denied such a vision. The truth is that she feared setting eyes on our son.

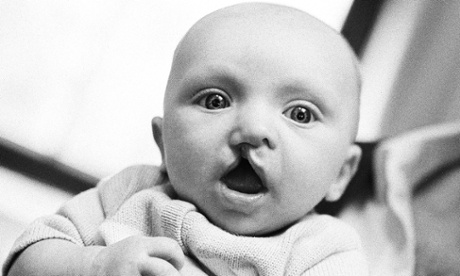

Hugo was born at home, as had always been our plan. (His cleft, we were assured, made no difference to the birth.) It was a long and difficult labour – nearly 20 hours – but the final stages went smoothly. When Hugo made his way out into the birthing pool, and the midwife lifted him out of the water, the right side of his face was facing away from us both. Gudrun hurriedly asked the midwife: “Can you see his lip? Does he look OK?” Unable at this stage to see his cleft, I remember, absurdly, thinking for an instant that the scans must have been wrong after all, that his face was unblemished. “He’s gorgeous,” the midwife said, and then turned him round so that we could see him properly.

He did look a bit funny. Because of the cleft, his lip curled up and his little mouth was almost a triangle. But what we both found surprising was how unimportant it was. Neither of us experienced any shock or revulsion. Rather, what occurred was an instantaneous downgrading of the problem. No sooner was the defect apprehended than it was accommodated, accepted. After all, it was a part of him – such a small part really. As such, and straight away, it became another thing to love.

About a decade ago, cleft treatment in the UK was overhauled. Instead of local hospitals treating patients on an ad hoc basis, regional cleft units were established in major hospitals. The care, for the first time, became properly joined up and specialised. The result is that Britain today is a world leader in the treatment of clefts. There are few better places in which to be born with one.

It also means that for all his misfortune in having a cleft, Hugo is fantastically lucky. He has access, for free, to the best possible treatment, and will do for as long as he needs it. I sometimes think about what his life would have been like had he been born in a poorer country, or in Britain but at an earlier stage of its development. As his parent, I find this hard to contemplate.

For most of history, a cleft has guaranteed a wretched existence – or indeed no existence at all, since one common way of dealing with clefts has been to murder those born with them. In ancient Rome and Sparta, babies were drowned or left out in the wilderness. In parts of Europe in the middle ages, clefts were seen as offering proof not just of the child’s satanic nature but of the mother’s too. (Accordingly, both mother and baby were often done away with.) This misogynistic association with evil is reflected in the confusing origins of the term “hare lip”. Although first coined because of the supposed resemblance between an untreated cleft lip and a hare’s mouth, the name became bound up, in the 16th and 17th centuries, with the superstition that witches often took the shape of hares. If a pregnant woman was startled by a hare, the theory ran, her offspring would bear a “mark” in the form of a facial abnormality.

Even when children with clefts made it through infancy, their lives, in the past, can’t have been good. Although cleft lip repairs weren’t unknown before the 20th century – the earliest recorded one was in China around 400BC – they were inevitably crude, and left a severe disfigurement. Palates, meanwhile, generally went untreated until the mid-20th century, guaranteeing, among other things, lifelong problems with speech. One effect of such shortcomings was that there was little check on prejudice. Ignorant assumptions about those with clefts – that they were subnormal, malevolent, a curse – received apparent confirmation in physical fact.

Today, while the situation in wealthy countries is much improved, in many poorer regions things remain dire. Ignorance and superstition are still widespread. In most developing nations, there is no state provision for repairing clefts, which leaves responsibility for tackling the problem at the doors of charities. The true severity of the problem isn’t always easy to ascertain, because, almost by definition, things tend to be worst in the places where record-keeping is patchiest. For example, any cleft charity worker will tell you that infanticide remains a problem in some poor and remote regions – in northern India, parts of sub-Saharan Africa. But gaining an accurate sense of scale is nigh on impossible, both because births in such areas aren’t adequately recorded and because those responsible have an interest in concealing the practice.

The tragedy is that, with recent developments in surgery, the problem shouldn’t be that hard to fix. Clefts are, in many ways, an unusual disability in that their severity is massively treatment-dependent. The exact same condition that could prove life-threatening in rural Nepal is no bar to a happy life in a well-resourced country. Yet the barriers, as ever, are willpower and money. Charities can’t do all the work, and many governments in developing nations question the wisdom of devoting resources to clefts. After all, they argue, aren’t there more pressing needs? When millions are starving or lack proper sanitation, when Aids and malaria are still rampant, how much of a priority should tackling clefts be?

In August this year, I went to India to learn about the work of Smile Train, the world’s biggest cleft charity. (The second largest, somewhat confusingly, is called Operation Smile.) It is responsible for around 120,000 cleft repairs a year in as many as 87 countries. It was founded in the US in 1999 when a group of business people got together with the idea of forming a charity. “We started with two ideas in our minds,” Satish Kalra, its chief programmes officer, whom I met in Delhi, recalled. “First, we wanted to focus on just one thing, because we knew we couldn’t solve all the world’s problems. Second, we believed that good management mattered more than good intentions. We didn’t set out to be Mother Teresa.”

Smile Train’s founders alighted on clefts, according to Kalra, largely because, to their business-oriented eyes, they represented an irresistible financial proposition. “Here was a problem that is fixable. Individual cleft operations are not that expensive. You could cost them down to the last dollar. And yet we knew that every one of those dollars would have a transformative impact on someone’s life. Our experience had taught us that success in business is all about extracting value for shareholders. You could say that, in charity terms, clefts offered an unrivalled return on investment.”

Various principles, Kalra continued, were “carved in granite” at the outset, the most important – and radical – being that Smile Train would never use foreign doctors. Other cleft charities followed (and continue to follow) a “missionary model” of provision, whereby teams of foreign doctors are dispatched to developing countries to carry out as many repairs as possible. Smile Train’s founders vowed never to use this approach. “If you’re there for a week, how many operations can you do? Twenty? Fifty? In a country like India, where 35,000 children are born with clefts each year, it makes no real difference. So we said we’d work only with local doctors. We’d train them, give them the necessary equipment, pay them for their work. In medical terms, we’d leave every country in a better state than we found it in.”

Two other key founding principles, Kalra continued, were that quality and safety would never be compromised – “A baby born in Bangladesh is just as precious to its mother as one born in New York” – and that Smile Train would be the “leanest charity in the world”. Kalra himself was responsible for setting up the organisation’s Indian division in 2000. (Smile Train had performed its first repair, in China, the previous year.) “To begin with it was just me working alone in this very office,” he recalled. “I recruited my first doctor, then another. We grew and we grew.” In the ensuing 15 years, Smile Train has undoubtedly made a huge difference in India. It now has 180 centres across the country and performs around 46,000 procedures each year – easily more than half of the country’s total cleft repairs. Currently, almost all the money for these operations comes from the charity’s fundraising in the west, mostly in the US, but it aims to transfer the financial burden to India. “Eventually we want India to pay for India, China to pay for China, and so on,” Kalra said. “That way, what we do will start to become sustainable.”

After meeting Kalra, I travelled to Kerala, in the south, to visit one of Smile Train’s treatment centres. The Jubilee Missionary hospital in the city of Thrissur (pop 316,000) is a Catholic hospital built in the 1950s. From the outside, it’s a sprawling modern structure; inside, it resembles what I imagine a British hospital might have been like a century ago. There’s a marked lack of equipment – the wards consist of rows of rickety single beds and little else – and the lighting is poor. Nuns in starched costumes walk about holding tottering piles of linen.

Yet in this unpromising environment, what has taken root is impressive. The hospital is home to the Charles Pinto Centre for Cleft Lip and Palate, which is presided over by an 85-year-old surgeon named Hirji Adenwalla. The centre predates Smile Train: Adenwalla founded it in 1959, naming it after his former boss. For the next four decades it was a one-man department; then, in 2000, its fortunes were transformed when Smile Train arrived on the scene. Today, it is a flourishing multidisciplinary department with six full-time surgeons, two speech therapists and an orthodontics unit. It has also helped make Adenwalla a well-known figure in cleft surgery. He regularly attends conferences around the world. “I got recognition by chance, through Smile Train,” he told me with typical modesty.

When I arrived, Adenwalla was conducting an outpatient clinic in a room cluttered with tables, old medical tomes and filing cabinets. Adenwalla, dressed in shorts and a short-sleeved shirt, sat at the central desk, with members of his team ringed round him in descending order of seniority. (Everything about the hospital was intensely hierarchical – something else that made it feel like a time warp.) Hanging on the wall behind Adenwalla were some 50 photos, mainly of white middle-aged men. These, he explained, were his heroes: the doctors responsible for developing and refining cleft surgery. He talked about them as if they were friends. “There’s Peter Randell, a truly great man. And there’s Murari Mukherjee, responsible, of course, for the Mukherjee flap.”

The patients came in, accompanied by their parents (usually both mother and father but sometimes just mother). Many of the mothers wore hijabs; one wore a full niqab, with just her eyes visible. Most spoke no English. “Although Kerala is a majority Christian state, we find that most of our patients are Muslim,” Adenwalla told me, before cheerfully explaining that the high incidence of “consanguinity” in Muslim communities led to a greater number of clefts.

The patients varied in age: some were small babies, there for their first operation; others were older, returning for check-ups or because they needed a second, third or fourth procedure. One boy with a badly misaligned jaw was 17. One seven-year-old girl had the worst cleft I’d ever seen – a rare variant of the condition where the cleft goes up into the eye. She’d had eight operations and would need many more. By western standards, all were poor – Smile Train only helps those who can’t afford the $300 or so a cleft repair costs in India – but Adenwalla pointed out that, compared with many, they were quite well off. Kerala is a wealthy state: even the poorest have decent homes; literacy rates are high. This makes Smile Train’s job easier. “The people here, if you give them a date for treatment a year in advance, they will turn up on the exact day,” Adenwalla said. “In the north, it’s very different. Families may have to travel for days to get to a centre, and they decide they can’t spend the time away, even if Smile Train is going to pay their travel costs. Or we do a child’s lip, tell the parents to come back in six months for the palate, and we never see them again.”

I was struck by how compliant the parents – and their children – were. A photographer was present, and as each child appeared, he snapped away. None of the parents were asked in advance if they minded. In Britain, if this happened, there would (quite properly) be outrage. Here no one objected. The families unquestioningly did whatever Adenwalla – who, I realised, was regarded as a saint – asked of them.

Next day was surgery; I sat in. The most fascinating moment, for me, was watching Adenwalla’s second-in-command, Puthucode Narayanan, perform a lip repair on a five-month-old girl called Safia. (On her file, oddly, it said she had “no name”; I later found her mother and she gave it to me.) In contrast to the rest of the hospital, the operating theatre was full of modern equipment; in fact, I recognised the monitor Safia was hooked up to from ones I’d seen in Britain. “Yes, this equipment is all state of the art,” Narayanan said. “But we wouldn’t have any of it if it wasn’t for Smile Train.”

Dressed in scrubs, I sat to Narayanan’s left. Safia, already anaesthetised, was positioned with a cushion under her shoulders and neck, so that her head was tilted back. A medical sheet was placed over her, with a hole just for her mouth and nose. Somehow, while the operation lasted, it seemed important not to see the whole of her, to be able to forget that she was actually a person. Narayanan began by drawing an intricate web of lines on her nose and upper lip. “These are the cuts I’m going to make,” he said. In the old days, he explained, cleft repairs had been little more than an attempt to close a hole. “The result looked terrible; everything would be twisted.” The basis of modern cleft surgery, he explained, was the principle of rotation. “You cut flaps and then use those to pull the parts round into the correct position, so that things align properly.” The operation he was performing that morning, he added, was a “Millard repair”, after the pioneering Chicago-based plastic surgeon Ralph Millard.

With a degree of composure that I could only marvel at, Narayanan proceeded to cut into Safia’s nose and upper lip along the lines he’d drawn. Within minutes, her face (or the part of it that was exposed) had been opened up, deconstructed. Bone was visible; the nose was no longer there. In a different context, watching this would have been unbearable, but somehow the clinical atmosphere – the sense of concentrated normality – meant it wasn’t too bad. (Also, another Smile Train gizmo – a computerised cauterising machine – ensured that there was surprisingly little blood.) And Narayanan himself was a calming presence. As he cut, he talked – first about the operation, but then about other matters. During a particularly intricate phase, we spent several minutes discussing the previous month’s Wimbledon final. (“Such a shame Federer lost. What an elegant player!”)

Once the cuts had all been made, and the whole middle section of Safia’s face gaped open, Narayanan announced: “Now for the last bit.” And he proceeded to stich the various flaps he’d created back together. As he did so, a miracle occurred. The same face as earlier reassembled itself, but this time without the cleft and the lopsided nose. Everything was in its correct place. Safia looked very much like Hugo had after his first operation. I found myself fighting back tears.

Before Hugo was born, Gudrun and I assumed that the hardest thing to deal with would be what he looked like. In fact, we were wrong. Those first few months, before his lip was repaired, there were a few times when I noticed people recoiling from the sight of him – a woman serving in a delicatessen; a man jogging past when we lifted him out of the car. But once his lip was fixed, this quickly stopped. Within a couple months, the scar had healed and was no longer readily detectable. Aside from a slightly wonky nose – which was also something you wouldn’t necessarily notice – Hugo looked normal. He became, to our wonder and gratitude, a good-looking boy.

Instead, the bigger difficulty was speech. Hugo’s palate was operated on just after his first birthday. He became an immensely chatty toddler. From the age of about one and a half, he developed an obsession with cars, and soon learned to identify all the major (and, in time, minor) makes. The first one he learned was Mini, which he could say more or less perfectly. But others were less readily comprehensible. BMW was a strange concoction of vowels and glottal stops, unrecognisable to all but his parents; Honda was “Onna”; Porsche was “Orrs”. It became clear that Hugo had very few consonants; the only ones he could properly enunciate were M and N. This, we learned, was because his palate simply couldn’t do one of its main jobs, which is to close off air to the nose. Without the ability to do this, making hard consonant sounds – P, D, K and so on – is impossible.

So just before he was three, Hugo had a third operation, to elongate his palate; and then, six months later, he had another, more minor one. For the past two years, he has had regular speech therapy (courtesy of our local cleft unit). And gradually, but surely, the sounds have come. Instead of being understood only by those who know him best, Hugo’s speech has become comprehensible to more or less anyone. It isn’t yet perfect – the therapy continues – but we are confident that, when he starts school next year, he will not be at any significant disadvantage.

Hugo’s cleft is part of who he is, and always will be – I wouldn’t want him, or us, to try and pretend it away. Down the line, there will be further treatments: an operation on his gum that will involve taking a bone graft from his hip; significant orthodontic work; an operation to straighten his nose; perhaps other things too. Yet such procedures, which seemed so momentous, so scary, when we first learned about his condition, now seem like little more than minor inconveniences. As a parent, you do what you have to; you also know that you would do anything. So the occasional stay in hospital, frequent check-ups – these come to seem like trifling sacrifices, no drain at all on the reservoir of your love.

I don’t find it easy, now, to look back on the period just after we learned about Hugo’s cleft, to know that we came so close to not having him. Thankfully, we made the right decision. I feel stupid for wavering, but I also know that, at the time, we were hampered by our ignorance. And perhaps, too, by more general failings. If clefts had been more known about, more widely discussed, then maybe we wouldn’t have been so thrown, so impressionable. And surely it would have helped if we’d lived in a society less in thrall to the idea of physical perfection, more at ease with the idea that everyone is different. Certainly, having a child with a cleft has given me a new perspective on our society’s attitude to those with disabilities, and on the oddity of a culture which has normalised going under the knife to try and attain a prevailing, and very limited, idea of beauty.

Hugo turned four last week. We gave him a bicycle – an ordinary present for a boy whose life is, for the most part, gratifyingly normal. There’s no doubt that he will face significant challenges in the future – not least the necessity of coming to terms with the fact that, at least when he was born, he did look different. Yet knowing who he is, seeing the person he’s becoming, I don’t doubt that he will surmount these, and other hurdles, with ease. In time, I hope that he may even come to look on his cleft with something approaching gratitude, for the schooling it gave him in one of life’s most important lessons, which is that none of us is ever perfect.

For more information about Smile Train, or to make a donation, go to smiletrain.org