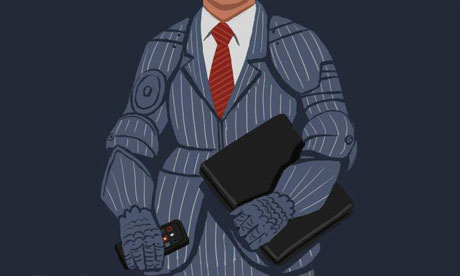

The killing of Osama bin Laden triggered a surge in Amazon sales for a book entitled Team Secrets Of The Navy Seals: The Elite Military Force's Leadership Principles For Business. You can imagine the typical purchaser: an executive – I'll take a wild guess and say a male executive – excited by the notion of "storming the compound" of their industry and shooting their competitors in the face. (Metaphorically, of course, since today's rather tedious health-and-safety culture tends to frown on actual face-shooting.) But this isn't new: for years, the shelves have heaved with titles offering business tips from Lord Nelson, Ulysses S Grant, Norman Schwarzkopf, Attila the Hun ("timeless lessons in win-directed, take-charge management"), the marvellously named Colonel Thomas Kolditz, and various other angry-looking gentlemen of the kind played in movies by Chris Cooper.

Whatever your attitude towards the military, there are obvious problems with this genre. The failings of military bureaucracy – non-working rifles going unreplaced for months, etcetera – are commonplace in the news, while the US army, specifically, is demonstrably dysfunctional, with rising suicide rates now higher than among civilians. (To its credit, the organisation is responding with a major anti-suicide initiative involving the leading "positive psychologist" Martin Seligman.) But scrutinising the military for non-military purposes is also a respectable field of study in business schools. And what's fascinating is how surprising its findings might prove to the testosterone-addled executive, intent on becoming a workplace general.

For a start, there's no place for relentlessly pursuing bold goals and damn the consequences. The military approach known as "scenario planning" is by contrast profoundly cautious, intent on visualising worst-case outcomes, ever alert to the high likelihood of failure. It has to be. Likewise, Sun Tzu's endlessly cited Art Of War is really a manual of Taoist spirituality, about victory not through imposing your will but by gracefully bending to changing reality. "Take-charge management" is out, too: modern military thinking, if not yet practice, is obsessed with empowering frontline troops, who are usually best placed to take decisions mid-battle. Two Marines, Timothy Saint and Nicholas Smith, suggest the following useful bias: if a subordinate's plan is at least 60% as good as yours, go with the subordinate's: he or she will execute it twice as well, just through feelings of ownership.

The real problem, though, is revealed in the embarrassed caveats that pop up throughout such works. "Clearly," as one Harvard Business Review piece puts it, "the danger for a business leader who is trying to reach an agreement with a single-source supplier… differs from that for a soldier [seeking] intelligence on the source of rocket attacks…" And inspiring your employees, concedes Businessweek, "is a little easier when your job is to stop innocent people from being butchered [than] when you're implementing a new IT system." Bingo. Life-or-death situations can induce great clarity, calm and insight. But vigorously trying to pretend you're in one – when you and everyone else can see you're not – is surely a recipe for stress and tension, and a distraction. Many people have to risk their lives for their work. If you don't, why not be grateful? Putting yourself needlessly in the firing line is silly – and, incidentally, something a well-trained soldier would never do.

oliver.burkeman@theguardian.com; twitter.com/oliverburkeman