There's a funny kind of hierarchy that exists among the organs. You simply don't hear bladder surgeons boasting about their art in quite the same way that heart and brain surgeons do. And yet, even the most humble body part has its own complex and fascinating physiology.

I realised this when learning about the structure and function of the stomach. Previously, I had thought of the tummy as a lowly place, a mere dumping ground for anything we might choose to stuff in our mouths. I couldn't have been more mistaken, and my new-found respect for the stomach gained focus when I read about the gastric pit.

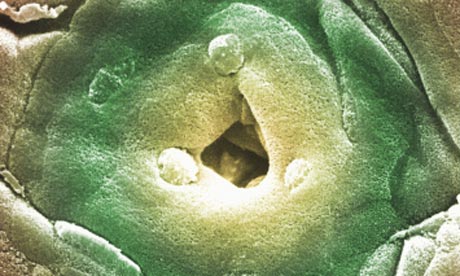

If you look inside a stomach when dissecting a cadaver, or during an operation, it appears like a bag whose surface is thrown into a series of visible folds. These are called rugae, and enable the stomach to increase dramatically in size when it fills with food. What you can't see with the naked eye is that the lining of the stomach (the mucosa) is interrupted by multiple tiny openings, each of which leads to a tiny hormone-producing tunnel. These are the gastric pits and each one is lined with a number of different types of cell, producing a separate, important gastric secretion.

The cells at the top of the pits produce mucus, which protects the stomach lining against gastric acid. Deeper down are two other cell types. Parietal cells generate stomach acid as well as a substance called intrinsic factor, which enables a vitamin called B12 to be absorbed further along in the gut. The impressively named chief cells secrete pepsinogen which, when it mixes with stomach acid, becomes an enzyme called pepsin. This helps to break down the protein we eat into smaller units that can be absorbed.

The heart may be in charge of pumping blood around the whole body. The brain may be master of all we do. But, at the tissue level, wonders are also to be found in those organs that we may think of as being more ordinary.

Gabriel Weston is a surgeon and author of Direct Red: A Surgeon's Story