Read wisely and widely, literature will usually provide answers to the great mysteries of the human condition. Except when it comes to how to maintain an active sex life in a monogamous relationship; on that the great – and the not-so-great – novelists are almost entirely silent. Until the end of the 19th century, sex was not something that was deemed appropriate reading matter for the middle and upper classes: chaste kisses and lingering looks that hinted at raging desires were about as racy as it got.

Even if Jane Austen had been free to write about sex, it doesn't seem as if she would have had much enthusiasm for it. The pleasure in Pride and Prejudice is all in the social twists and turns, the will-they-won't-they-of-course-they-will, with Elizabeth and Darcy's wedding merely the pay-off.

When novelists did turn their pens on married couples, it was almost invariably to examine the end of these relationships rather than to dwell on their fulfilment. Rather than looking for new ways to revive her marriage to the desperately dull Karenin – as a modern-day therapist might suggest – Anna eventually runs off to find new levels of unhappiness with her lover, Vronsky. So too, Emma Bovary, who ditches her boring, provincial husband, Charles, for the more exciting Leon, only to end up dosing herself with arsenic when the affair has run its course. However much you may feel for these great heroines, death is the price they have to pay for having indulged their lust. The morality of the era demanded nothing less.

Women fared little better even with the birth of modernism and proto-feminism in the 1920s. Virginia Woolf's Clarissa Dalloway is stifled within a moth-balled marriage; she does not seek to improve her relationship with Richard, nor does she surrender to the possibility of an affair. Rather she sublimates her desires into the niceties of proper manners: Mrs Dalloway's punishment is a living death.

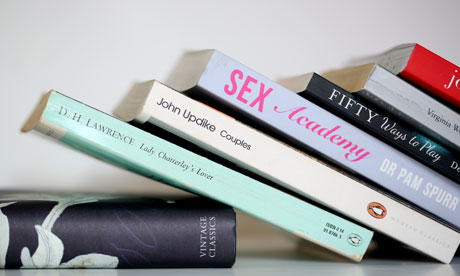

Throughout all these novels, sex was still implicit, with the focus on the consequences rather than the deed itself. A blessing, perhaps, given how many writers have subsequently written so badly about sex. And when it was up for grabs – as it were – the future of monogamy didn't look any less bleak. Constance Chatterley longs for "an integrated life" – a euphemism for a decent sex life – but is denied it with her husband who has returned disabled from the war and she can only achieve it with Mellors, the gamekeeper – a commoner who has not lost touch with the Earth, Nature and, most importantly of all, Capital Letters.

Even with the sexual liberation of the 1960s, marriage was the kiss of death to most novelists. Couples – typified by John Updike's Couples – existed in fiction primarily to be unfaithful to each other. One of the few modern writers to have attempted to portray a long-term happy marriage with a fulfilled and active sex life is Ian McEwan in Saturday. Almost certainly unintentionally, though, Henry Perowne, the neurosurgeon protagonist, emerges as one of the more annoying characters in 21st-century fiction as he does everything so perfectly – including make love to his wife so they always have simultaneous orgasms – that it's hard not to dislike him. Other people's sexual and emotional success does not always make good reading.

And so, counter-intuitively for an act that is revered for its creative spontaneity, it has generally been to non-fiction that the curious have been forced to turn for sexual self-improvement. The first widely read sex manual was Marie Stopes's Married Love, published in 1918, a revolutionary feminist text in which women's sexual desires were treated on a par with men's. The book was banned in the US and scorned in the UK by its mostly male reviewers, but still sold 750,000 copies by the time the US censor allowed its publication in 1931. By today's standards, though, it is fairly tame. As a guide to informing women they had a right to expect more than statutory rape on their wedding night, it was invaluable; as a means of achieving sexual satisfaction, it was still groping between the sheets.

It did, however, establish the sex manual as a genre. In 1934, the philosopher novelist Arthur Koestler, writing under the name of Dr A Costler, wrote the first of a trilogy of sexual encyclopaedias, complete with monochrome illustrations and colour plates. Whether he was quite the man to be handing out this advice is rather more debatable, as he was subsequently revealed to be a rapist, who defended his actions in a letter to his second wife by saying, "without an element of rape there is no delight".

The real breakthrough for sex manuals into the mainstream came in the early 1970s when The Joy of Sex spent more than a year in the top five of the New York Times bestseller lists. The aim of the book was to do for sex what recipe books had done for cooking, and bring a range of delights beyond the missionary position into the bedrooms of those who had heard of the sexual revolution but never encountered it.

The style was chattier and less clinical than previous manuals – less emphasis on "inserting X into Y" – but there was still something quite joyless about The Joy of Sex. In large part this was down to the illustrations, which made it look as though adventurous sex was the preserve of a consenting woman in Birkenstocks and an earnest bearded teacher.

Four years ago, The Joy of Sex was updated with a racier text and rather more joyful images, and it remains the basic textbook for anyone whose sex life may be stalling but is not yet ready to see a relationship counsellor. After opening with the point that sex is an expression of intimacy rather than something that might occasionally lead to intimacy if both partners have downed the necessary units of alcohol, it doesn't kill all the fun by going on and on about the importance of talking about your feelings at all times.

Rather, The Joy of Sex is a cookbook, complete with a list of possible ingredients, appetisers, main courses and "sauces and pickles", leaving you to pick and choose. If you want to avoid the finer points of "ben wa balls" – (me neither) – "skin gloves and thimbles", "boutons", "ligottage" and "les anneaux", then the author isn't going to think any the worse of you.

And that's rather my problem with Dr Pam Spurr – she of Loose Women and This Morning – whose Sex Academy is one of the new generation of manuals that tells it as she sees it. Unfortunately, she recommends a series of lessons and rules that, for those of us whose school days were punctuated by failure and detentions, is a bit of an initial turn-off. But for over-achieving, competitive, alpha couples who like nothing better than to mark each other's daily contribution to their sexual wellbeing, Dr Pam should tick most of the boxes.

The less said about many of the other manuals that fell across my desk, the better. The Manhattan Madam's Secrets to Great Sex should probably have been renamed, How Every Woman Should Be a Hooker in Bed, seeing as its subtitle is Expert Advice for Becoming the Best Lover He's Ever Had. That's right, women! You'd better shape up for us stud muffins or you're toast! And don't even think of offering me advice on becoming the best lover she's ever had because I already am.

Inevitably, too, Fifty Shades of Grey has spawned its own mini industry of How To guides. For those with an interest in BDSM, Fifty Shades of Play offers an in-depth guide to flogging instruments, electrostimulation, crotch ropes and torture. Step 50, by the way, is "Aftercare". Thanks, but no thanks.

Still you can't say that there aren't now manuals on the market to cover every arcane sexual avenue. Sex manuals are now big business. Serious business. Though how serious is still, mercifully, up to you.