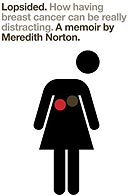

Lopsided: How Having Breast Cancer Can Be Really Distracting

Meredith Norton

Virago £11.99, pp224

My Diary

Mio Matsumoto

Cape £12.99, pp200

Cancer is capricious. It picks on the young, the funny and the bright as much as on anyone else. Like a primitive god, it is random, disorderly and self-regarding. The growing number of cancer memoirs represents an attempt to impose order on lives taking off in unwanted directions. They tap into a curiosity to know what the extraordinary - but also utterly ordinary - business of cancer is like, what it means to live more openly than the rest of us with death and chance.

Which is not to say that all cancer memoirs are equally illuminating. Cancer also stalks the smug and the boring, those who think that wheatgrass juice or belief or their sheer specialness is going to get them through. Meredith Norton slyly alludes to this when she describes trying to read Lance Armstrong's bracing cancer book during her own treatment for third-stage inflammatory breast cancer. 'I bet,' she says, contrasting his success in all fields with her own feelings of inadequacy, 'he doesn't still debate what he's going to be when he grows up. I doubt that he looks at his own kids and wonders when someone else is going to pick them up.'

At the beginning of her memoir, Lopsided, the African-American Norton is living in Paris with her French husband and infant son. Concerned that one of her still lactating breasts has become 'huge, throbbing, covered with a red rash, and radiating enough heat to defrost a frozen lamb shank in 10 minutes', she sees four doctors in France, who all dismiss her symptoms. She flies home to California for a fifth opinion, where she gets a prompt diagnosis and is given a 40 per cent chance of still being alive in five years.

Norton's engrossing memoir is droll and sometimes prickly. On hearing the results of her cancer test, she notes that two strangers had just witnessed something more intimate for her than losing her virginity or giving birth. 'Death is really the only thing you do alone, no matter who is there to hold your hand. These spectators watched as I visualised my death, with probable accuracy, for the first time. And the picture was so banal.' She slips in her insights quietly, with novelistic precision.

The writing is determinedly wry and unsentimental, but real feeling seeps through. Her portrait of her affluent, noisy family is vivid and affectionate, conveying their warmth and support along with their rectitude (her father, a urologist, still corrects his adult children's grammar). When the family is gathered around the dinner table arguing loudly about how many crackers her brother can eat, her sister leans across and whispers: 'Please don't die and leave me alone with these people.'

Underlying the playfulness, though, there is a dragging sense of sadness, which no amount of humour, bathos or what Norton calls 'my own school of psychology, the School of Repression', can extinguish. She was in her thirties when she developed cancer, still convinced she was destined for great things when she could get around to them.

Her husband Thibault, complete with a French aristo sense of entitlement summed up by 'his unpronounceable, mostly silent-lettered medieval name', wants his wife's illness to teach them something, to supply some sort of revelation. 'Instead,' Norton acknowledges glumly, 'there we were, with the same annoying habits and bad manners, ungrateful, pessimistic, undisciplined and bored'. The only revelation seems to be that 'there might be no lesson in this experience; it might just suck'.

Mio Matsumoto was even younger than Norton when she developed cancer, still a student at the Royal College of Art. At first, she thought she had an ulcer on her tongue, then a boil; when she eventually sought the advice of a doctor, in July 2002, she found she needed a biopsy. She decided to fly home to Japan. My Diary is her mainly pictorial account of her treatment over the next five months, expressed in quirky line drawings with scribbled words beside them.

The book's charm, and its poignancy, lies in the contrast between Matsumoto's girlish preoccupations and the indignities of treatment - laxatives and enemas, having to suck spit out of her mouth with a tube. A hopeless love affair in London, a crush on one of the doctors, her discussions with friends about how rubbish she is at picking boyfriends; these things cease to be silly and seem, instead, like a life to which everyone should have a right.

In common with Norton, Matsumoto quickly realises that having cancer doesn't make you a better person. She is forever rowing with her mother about staying out at bars, then feeling remorseful. 'I wanted to carry on watching TV rather than keep talking endlessly,' she writes, next to a picture of herself slumped on the floor looking vacant. 'I know I'm a kid and a bitch.'

Mio Matsumoto is an accomplished designer, who has gone on to create packaging for Miller Harris and T-shirts for Marc by Marc Jacobs. Her quirky, playful drawings and the often slightly inept constructions of her scribbles - 'I was just being so lazy for two weeks by now' - are endearing and affecting. Taken together, these two memoirs tell us very little about cancer beyond the fact that it's absurd. Joking, as far as you can, may be one of the most rational responses. About human particularity, and the capacity for humour and charm, they tell us quite a lot.

· To order Lopsided for £10.99 or My Diary for £11.99 with free UK p&p, go to observer.co.uk/bookshop or call 0870 836 0885