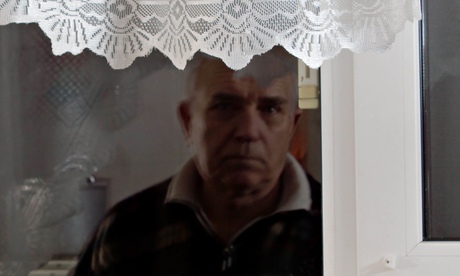

The first step in responding effectively to loneliness is to understand what it is. Loneliness is where the quantity or quality of our relationships doesn't match our expectations. This definition indicates the subjective nature of loneliness, but also reflects the importance of social relationships to individual wellbeing.

Loneliness tends to be associated with older age, especially when people retire (social loneliness), lose a loved one (emotional loneliness), or can no longer access transport. Public managers in care services are familiar with the more acute aspects of loneliness, especially in later age where loneliness correlates with negative health outcomes.

The link between subjective wellbeing and health is now established, although we still need more co-ordinated action to respond to it effectively. The Campaign to End Loneliness is a network of organisations and and individuals, launched in 2011 by five partner organisations including Age UK Oxfordshire, Independent Age and Manchester city council, to create conditions that reduce loneliness in later life. It has published guidance for local authorities and health and wellbeing boards, explaining why loneliness is a problem, and what can be done about it. Many of the campaign's examples focus on prevention, and include interventions such as Age-friendly Manchester and various befriending services.

However we shouldn't view loneliness only in terms of negative health outcomes. Local authorities and other public services should ensure existing services reach those more at risk of loneliness, and develop services that directly tackle loneliness, ranging from bereavement support to transport services.

Perhaps surprisingly, according to research by the insurance company Aviva 18- to 24-year-olds report the most loneliness. This may be explained by the disruption of social ties as they finish school, but also because work environments offer less meaningful social interactions for young workers.

Other groups further undermine the conventional notion of loneliness. Black and minority ethnic people generally self-report higher rates of loneliness, even among groups perceived to have larger and closer families, again suggesting that the quantity of social interactions is not the most important measure. Another important conclusion to be drawn from high minority ethnic loneliness is that addressing poverty and inequality may also reduce loneliness.

In a second area, public managers can respond to loneliness that their employees may be experiencing or to caring that staff are having to undertake outside work as a result of a family member or friend who is at risk of loneliness. In the latter case, public managers need to make flexible working a reality, allowing more sabbaticals or extended leave from work, even if these are unpaid and extending bereavement leave.

It may be tempting to respond directly to loneliness among employees through team-building exercises or after-work social events. But what really matters is the quality of relationships, so people may not wish to have more social interaction with colleagues where these interactions are not meaningful enough to lessen their loneliness.

The clear health consequences of loneliness among older people and the public service possibilities for addressing it mean the challenge is to ensure subjective wellbeing (and prevention of loneliness) is taken seriously in the distribution of scarcer resources.

Public managers must also, however, understand the wider experience and effects of loneliness across their employees and service users. People should have greater opportunity – and time – to develop and nurture meaningful social relationships outside the workplace with people they care about.

• The new Guardian Society Professionals website for people working in the public services is revisiting Beveridge's five giant evils of the welfare state. Loneliness has been identified as one of the modern evils facing public services. Join us tomorrow to debate what society professionals can do to tackle it theguardian.com/society-professionals