In Henry James's 1893 short story "The Private Life", the narrator makes alarming discoveries about two members of his holiday party while holed up in a village in the Swiss Alps. After an evening spent listening to the table-talk of the London playwright Clarence "Clare" Vawdrey, he steals up to Vawdrey's room where he sees, "bent over the table in the attitude of writing", the man he thought he'd left downstairs in the company of his friends. Vawdrey, it seems, is double: there is his public self, which according to the narrator is burdened by "neither moods nor sensibilities", and his private, writing self, which remains hidden.

The effortlessly suave raconteur Lord Mellifont, meanwhile, suffers from the "opposite complaint". He is "all public", the narrator says, he has "no corresponding private life". There's nothing behind the pristine mask of his public self: Mellifont is all performance.

Josh Cohen discusses this story in his elegant and suggestive book. For him, James's tale can be read as a premonitory parable of the modern culture of celebrity, at the centre of which is the public's apparently insatiable demand for celebrities to be "no more or less than they appear" – that, like Lord Mellifont, they show us everything. Celebrities themselves collude in this demand and go to considerable lengths, as Cohen puts it, to "disappear seamlessly" into their public persona. They persuade their acolytes that there's nothing left over, no private remainder that, Vawdrey-like, they keep locked away from prying eyes.

This, Cohen argues, is the self-defeating logic of the superinjunction. Self-defeating because, as with the gagging order taken out by Ryan Giggs in 2011, it arouses the very fantasy that the celebrity is seeking to suppress (in Giggs's case, that he had had an affair, and was no longer the willowy adolescent first spotted by Alex Ferguson).

And there's a further paradox here: by treating his private life as territory over which he had to assert ownership, Giggs encouraged the prurient to see it as a prize to be captured. Cohen argues that both sides in the contemporary war on privacy – celebrities and the tabloid press – take for granted a conception of privacy as property (that's why we routinely use the word "invasion" when someone's private life is pried into). The only difference is that one side, the tabloids, is indifferent to property rights. As the former News of the World journalist Paul McMullen put it in a memorable appearance before the Leveson inquiry: "privacy is for paedos".

Cohen calls this the "bourgeois" conception of privacy, since it's all about possession, in this case, of a self. But there's another, darker and more mysterious notion of the private life, he argues – the one bequeathed to us by psychoanalysis (Cohen himself is a practising psychoanalyst, as well as a literary academic). According to this view, "the ego is not master in its own house". We don't own our unconscious selves and psychic health requires us to give up the comforting fantasy of a self that is "integral and complete". We are all Vawdrey, in other words – whether we like it or not (and the demands we make on public figures suggests not).

You don't have to accept the entire conceptual apparatus of psychoanalysis to find all this compelling, and in any case, Cohen himself is attractively sceptical about some of the claims that Freud and others have made on its behalf. Cohen's prose has the aphoristic, epigrammatic quality that you find in Adam Phillips's writing about psychoanalysis, and he is less in thrall to his own fluency than Phillips is.

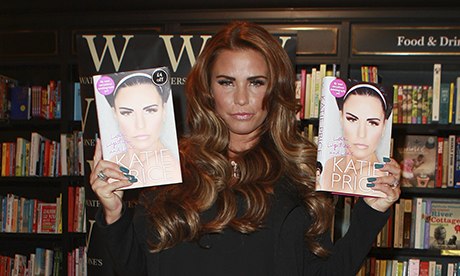

The range of references is impressive, too: Cohen is equally at home discussing Katie Price (below) as he is expounding the thoughts of Hannah Arendt. His analysis of the ur-reality show Big Brother is particularly interesting. Cohen suggests that what made the first series of the programme, broadcast in 2000, such compulsive viewing was not that it collapsed the distinction between public and private, but rather that it tantalised us with "the hope of encountering the invisible other, of burrowing into the obscure marrow of their everyday existence", putting the viewer in the position of James's narrator watching Vawdrey's double at his writing desk. Subsequent iterations of the show, Cohen suggests, sacrificed that quality by filling the house with "needy exhibitionists" and "parading the utter extinction of the very difference between the private and the public realm as entertainment".

There's a moral to be drawn from this about what Cohen calls the "modern malaise". It's not just about entertainment; it's also about our changing attitudes to our inner lives. What is it that connects the neuroscientists at Berkeley who want to map the neural activity of a dreaming person and put it on YouTube with the compulsive tweeter or the obsessive "lifelogger" who records and broadcasts her life, minute by minute?

What is at work is a powerful vision of a world without inwardness, one in which the external record of a life is the same as our experience of it. He quotes something the science writer John Brockman said about the "collective externalised mind" promised by the internet. For Brockman, that's not dystopia, it's utopia. Yet, as Cohen points out, there's another name for it: "totalitarianism" – the slogan of the Khmer Rouge, for example, was "Destroy the garden of the individual".

Cohen suggests that cognitive behavioural therapy, which has grown dramatically in popularity in recent years, nourishes a similar fantasy of total liberation from the burden of the inner life. What many people find so threatening about psychoanalysis, by contrast, is its insistence that the self is never whole. It tells us that our best hope, as Cohen writes at the end of this unsettling book, lies in accepting that part of us will forever remain in the dark.