The Alastair Campbell relaxing in an armchair in his airy north London home is not what people might expect. For a start, he is softly-spoken and subdued - not characteristics normally associated with the controversial former spin doctor. He is also content to talk at length about a subject many people would run a mile from - what it's like to live with mental illness or, specifically in his case, recurring depression.

"When you have got the dark cloud descending, life does feel pretty shitty," he says. "I regularly count my blessings. It's a really nice life, but if you get depression then it doesn't matter. This is what drives you crazy about people saying: 'What's wrong? What triggered it?' It doesn't matter. You don't know." Not waiting to be asked, he volunteers: "When did I last feel like that? Just after Easter for about three days. It wasn't bad bad bad. I woke up with a kind of numbness.

"What happened to me is a really important part of who I am and what I am," he says, recalling his breakdown at the age of 28 and the subsequent, although less debilitating, depressions over the years. "I really feel that quite strongly. Proud is the wrong word, but I certainly feel a lot stronger as a human being as a result of getting through it."

In fact, this contemplative, visibly older Campbell appears about as far removed as you could get from his public image as Tony Blair's bombastic bully-in-chief or that of the foul-mouthed fictional spin-meister, Malcolm Tucker, from the BBC's The Thick of It and its movie spin-off In the Loop, for which he inadvertently provided considerable inspiration.

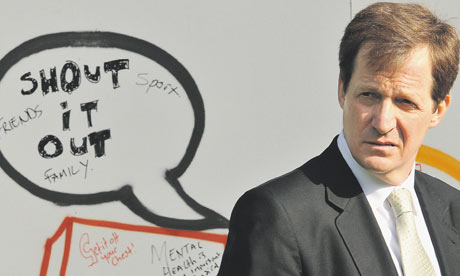

Campbell has had multiple incarnations before and since his days as a king of spin, including journalist, Leukaemia Research fundraiser, Burnley football fan, political diarist, blogger and, more recently, novelist. But he is currently basking in the glow of being named Mind Champion of the Year - in recognition of his latest guise as a mental health campaigner. He pipped TV personality Paul O'Grady, among others, to the post - thanks, he believes, to a last-minute "tweet" by Stephen Fry to get people to vote for him.

When In the Loop was released last month, Campbell was inundated with media requests to comment on how close to the mark the Tucker character was. He dismissed the comparisons out of hand. Nevertheless, how can someone with his bullying reputation end up with an award for championing the needs of people with mental health problems?

Campbell's response is unequivocal. He is adamant that both the media image of him and the fictional Tucker are far from the reality of life at No 10. "I think you've always got to differentiate between the media and the public," he says. "It's not the same. Look, there are some people who don't like you. There are some people who will have read the Daily Mail and believed and absorbed that, and therefore think I'm a terrible, terrible person, but I don't get that feeling as I go around the place. Most people don't think about me. I'm not on their radar."

So what about those who worked most closely with him? What would they say if asked? He pauses, as if it's never occurred to him that they might have been affected by his behaviour, then replies: "I think their first position would be, 'Well, you know that's not true.' I think you'd be hard-pressed to find people who worked with me who would say that. I wanted people to work hard, I wanted them to be committed, but I think I was quite good at spotting if someone was quite vulnerable. Obviously I am more conscious of it now, but I think I've had a sensitivity to it."

Campbell contends that much of the problem about his image rests with journalists, that they have often misread or misinterpreted his behaviour. Asked what he makes of a recent comment by one journalist that he was "the bully who sees himself as a victim", he responds calmly: "The ones who say 'he's a bully and a liar', when you actually ask them to come up with something that substantiates it they sort of blather on. I think with a lot of these journalists, an image develops. Well, there might be something in it. I have to accept I can be very aggressive, very full-on. I can be very combative - probably less than I was, because I have less reason to be."

Whatever the truth about Campbell's behaviour, or whatever its impact, his newly acquired credentials on mental health advocacy are impressive. His novel, All in the Mind, published earlier this year, has a mental health theme, and he admits that he drew very much on his personal experience of depression. In a recent BBC documentary, Cracking Up, he probed the evolution of his own illness with the help of psychiatrists, family and friends. And over the last couple of years, he has become more involved with Mind - although he insists that Leukaemia Research is "still my main charity" - signing on as a spokesman for the anti-stigma campaign Time to Change, speaking at conferences, and visiting mental health units. Taken together, it places him firmly among the ranks of celebrities and public figures such as Ruby Wax and Fry (winner of the same Mind award two years ago) who speak openly about their illnesses.

He has long been open about his past battles with alcohol, the breakdown he had while a young, fiercely ambitious hack on the Mirror, and his subsequent admission to a mental health unit. However, advocacy is a new departure, and if the response to his Mind award from posters on his personal blog is anything to go by, there are plenty of people queueing up to pat him on the back. One typical post says: "Thanks so much for what you do on this. You cannot imagine what it means for people to hear someone like you speaking out and admitting to your own vulnerabilities."

Normal life

It's comments like that, he says, that keep him at it, not any kind of grand plan. "The impact that you can have just in doing things that are just a part of your normal life ... There's nothing normal about living the life I led - going into politics, and then writing a novel - but having done it, and then seeing the impact it appears to have had on people ..."

He suggests that since most of his career has been about campaigning in some shape or form, he gradually realised it was a skill he could bring to bear. "If people within mental health charities think I can make a contribution that helps them meet their objectives ..." He says it is a "pain in the ass" that the media would rather speak to the famous than to ordinary people dealing with mental illness, but that if well-known people such as himself and Fry can act as a public face for campaigns, and the media sit up and take notice, then it's worth doing. "Charities try to generate interest, and that's what they're about and I think that's fine." Even the press have gone easy on him on mental health, he says, making it "the one area" where they haven't vilified him.

Two weeks ago, Campbell helped to launch Mind's latest campaign, focusing on men's mental health. As someone associated with machismo, it is perhaps not surprising that this area in particular interests him. He says: "There's no reason I can think of why men should be any less likely to get depressed than women, yet twice as many women are diagnosed with depression. Why? Because they are probably more open. Also they are more likely to go to see the doctor, and are more likely to take medication. At every level of that, men are resistant. You don't want to admit that something is wrong with you. You certainly don't want to admit that you've got some kind of mental weakness, because men are meant to be strong."

There is a natural confidence about Campbell when he speaks about his own experience or the issues he is particularly interested in, but he is less sure-footed on the details of policy. He says, predictably perhaps, that mental health has had greater priority attached to it under Labour, but adds: "Talk to people within psychiatric services and they still feel slightly Cinderella. I think it's shifted way up the priority order, but it's still got a way to go."

Constant awareness

When it comes to his own life, Campbell says it "has taken a lot of time" to accept that depression is simply something he has to live with. What he struggles with, he says, is the fallout on those closest to him. "The depression is bad enough, but the constant awareness that it's bad for other people as well makes it even worse," he says. "It's the old thing that you always hurt the ones you love."

There is a sense that Campbell regards the stigma often associated with mental illness as a particular burden, yet he believes we are at a "tipping point" and that society and the media are less and less likely to discriminate because of it. For someone so used to the limelight and so seemingly eager to court publicity, he feels nevertheless that there are things about living with depression that others will recognise in his experience when he says: "Sometimes it's just terrible, and sometimes you just have to say, 'Leave me alone.'"