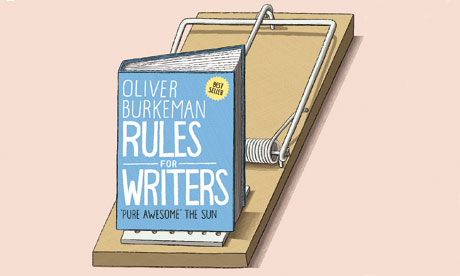

From time to time, I (not very earnestly) entertain the idea of releasing a book of "rules for writers" that would be deliberately terrible from start to finish, in order to nip the careers of aspiring rivals in the bud. My advice would be designed to exacerbate perfectionism, insisting on absolute silence, the perfect desk chair and specific brands of high-end stationery; it would urge people to wait for the Muse, and to compare their work, in detail, to those of the authors they most admire. Finally, in a Simon Heffer-ish touch, it would pompously assert the absolute unacceptability of certain grammatical forms, even though they're used by everyone from Shakespeare to Ian McEwan.

The depressing thing is that I think it might sell. Our appetite for books – and blogposts, articles and TED talks – offering "rules" for writing, or creative pursuits in general, seems limitless. Almost anything goes. Writers of genius offer rules so silly they must surely be joking ("Never open a book with weather", "Never use a verb other than 'said' to carry dialogue" – Elmore Leonard). Others offer rules that sound fruitful but aren't, such as this, from a popular video interview with the actor Rainn Wilson: "If you don't know who you are, or what you're about, or what you believe in, it's really pretty impossible to be creative." To which the blogger Austin Kleon retorts: "If I waited to know 'who I was' or 'what I was about' before I started 'being creative', well, I'd still be sitting around trying to figure myself out instead of making things." Perhaps what we really need, then, are some rules for interpreting all these so-called rules of creativity – so here goes.

First: it's best to interpret "rule" not as in law (a universal decree about how to act), but as in board games (a largely arbitrary constraint). People who rage at rules such as Leonard's tend to be using the former definition, but I'm fairly sure he intends the latter. An extreme version of this is "constrained writing", championed by the French group of writers called Oulipo: try, say, never using a specific vowel, or replacing every noun with the one seven nouns after it in the dictionary. The point is being bound by a rule; what the rule is barely matters.

Second: good rules act as correctives, not dictating behaviour, but reining you in from the opposite extreme. That's why they so often contradict each other. Should you seek randomness and spontaneity (as Ben Casnocha advises, with an excellent list of suggestions, or live a "regular and orderly" life, as Flaubert counselled, so as to free up energy for flights of imagination? There needn't be one answer. Which one describes you best? Try the other.

Finally, my personal, completely untested hypothesis: perhaps the main benefit of a good rule is simply distraction. Questions such as "How can I be more creative?" are intimidating, infinite and procrastination-inducing; rules give that part of your brain that's obsessed with such matters something harmless to do. Thus preoccupied, like a dog with a chew toy, it'll leave you unbothered while you actually get on with stuff. So should you really never use any word except "said" to carry dialogue, as Elmore Leonard suggests? "If it helps you get down to work!" I exclaim, perspicaciously.

oliver.burkeman@theguardian.com