The following correction was printed in the Guardian's Corrections and clarifications column, Saturday 17 April 2010

In Charlotte Raven's account of being diagnosed with Huntington's disease we misquoted Dr Nancy Wexler, president of the Hereditary Disease Foundation, as saying the sense of humour in those with the condition was robust yet infantile. In fact, Wexler said patients can maintain "an impressive sense of humour" until late in the illness.

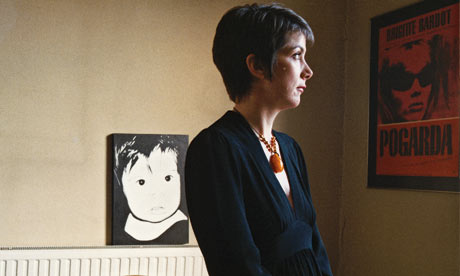

In 2006, 18 months after the birth of my baby, I tested positive for Huntington's disease. The nurse who delivered the news hugged me consolingly and left me with my husband and a mug of sweet tea to cry. In the days that followed, I began to realise why so few of the people at risk of inheriting this incurable neurodegenerative disorder chose to find out.

This incuriosity had seemed to me irresponsible. Having discovered the previous year that my father had the disease, I had been offered a test that would tell me for certain if I, too, had inherited the gene. In the months of debate I'd had with my husband about whether to take the test, I'd always been on the side of enlightenment. I calculated that the trauma of finding out would be offset by the satisfaction of being able to make informed decisions about my life.

I thought taking the test would be like finding out the weather before you go on holiday. If the outlook was gloomy, at least I'd know what to pack. In reality, it was more like finding out there was a bomb on the plane when you were already airborne. I felt impotent and envious of the uninformed majority. I wished I didn't know.

Following the diagnosis, I read everything I could find about Huntington's disease. Neurological psychologist Nancy Wexler – who had grown up with a mother suffering from HD and was therefore at risk herself – says Huntington's impacts on "everything that makes us human". Wexler is careful not to sensationalise her portrayal of the disease, but this affliction still reads like something dreamed up by the evil genius in a Batman comic strip. The symptomatology bore the infernal imprimatur of the Joker. What could be more testing than an illness that impairs quickly but takes decades to kill – or more cruel than one that robs you of your ability to communicate while leaving your capacity to understand intact?

The first visible sign of Huntington's disease is the chorea – jerky, uncontrollable, involuntary movements in all parts of the body. As parts of the brain degenerate, patients suffer severe cognitive problems: loss of memory, loss of judgment, loss of the capacity to organise oneself. Due to the loss of motor skills and the jerky, writhing contortions that afflict them, they find walking difficult and are prone to injury from falls. Patients lose the capacity to swallow and sometimes die of malnutrition. Their personality is often affected, too. Reports of aggressive, compulsive and sexually inappropriate behaviour are common. Towards the end, families often see no option but to have their suffering relatives institutionalised. There is currently no cure for Huntington's disease. Unsurprisingly, Huntington's patients often suffer from depression

At home with a toddler, the prospect of losing my newly discovered maternal feelings seemed particularly hard. The typical HD personality is demanding and unempathic – most unmaternal. I feared becoming an obstruction to be navigated round: a succubus draining life from the family host. I couldn't stand the thought of my daughter being scared of me. I pictured her dawdling at the top of the street on her way home from school, putting off the moment she would have to confront an irascible and unpredictable parent. I feared I might set fire to the house with her in it, like Woody Guthrie's HD-affected mother. Or parade in front of her schoolfriends in my underwear.

Having tested positive for HD, I was told it was inevitable that I would develop the disease at some point – but that it was not possible to know when. HD typically strikes in midlife. A fortunate few like my father suffer no symptoms until as late as their 60s, but for most it begins in their late 30s to mid-40s. I am 40 years old.

Frustratingly, some friends and family recast this certainty as a probability. "You might not get it," they would say, offering half-remembered quotes from articles about the neuroprotective benefits of fish oil. I began to feel like the only evolutionist in a room full of creationists. I understand why they do it. A hereditary illness for which there is no cure is a challenge to our sense of ourselves as self-determining entities. Having invested so much in the fantasy that we are authors of our fate, we would rather credit ourselves with the power to generate miracles than accept the incontrovertible evidence to the contrary.

The most up to date research on fish oil suggests that it does nothing to alleviate the symptoms or slow the disease's inexorable progress. Knowing this, my dad still takes 1,000mg a day.

My first suicidal thought was a kind of epiphany – like Batman figuring out his escape from the Joker's death trap. It seemed very "me" to choose death over self-delusion. Ah ha, I thought. For the first time since the diagnosis, I slept through the night.

I was shocked to read the figures for HD-related suicide. One in four people with the illness tries to kill themself. I was surprised it wasn't more. Rationally, you would have thought that everyone with the condition would realise the futility of continuing. Yet three-quarters of sufferers carried on. Why? Had they been duped by family members into believing they were not as far gone as they felt? Or were they falling for some misplaced belief in the sanctity of life? Their decision to cast the destruction of their identity and descent into madness as a challenge rather than a disaster seemed irrational, yet weirdly threatening.

I felt I had to argue them out of it. My mind clicked into gear, issuing bullet points to back up the case for self-destruction:

• If my cat had HD, I wouldn't make it carry on, but would get the vet to put it out of its misery.

• Without autonomy and the capacity for self-determination, life is meaningless. Merely existing isn't enough.

• Dependency is degrading.

• Suffering is pointless. The religionists' belief that it is spiritually instructive, and therefore an essential part of life, is dangerous and reactionary.

When Nancy Wexler's mother attempted suicide, her father discovered her and saved her life. His daughter says he later felt that saving his wife's life had been a "terrible mistake". He'd acted out of instinct, and subsequently regretted not respecting her wishes. If he had, she might have been spared the miserable years that followed.

I feared my husband would do the same. His opposition to my arguments in favour of killing myself when the time came was instinctual rather than intellectual. He couldn't offer any supporting evidence for his sense that a suffering, angry and dependent wife was better than a dead one.

He was right about one thing, though. My belief that he wouldn't be able to bear watching me suffer was, he said, a projection. I couldn't bear watching me suffer. I had already found myself wondering every time I misplaced my keys or failed to locate my phone charger whether this was the beginning of my decline.

I wanted to set a date. The first stages of the disease are often characterised by denial. Sufferers can spend the early years convinced there is nothing wrong. I feared that by the time I became fully aware of how bad I had got, I would no longer be physically capable of enacting my own death. I decided a pre-emptive strike would be necessary.

I pictured a room in the Chelsea hotel and me, still young and unscathed by the muscular spasms that contort the faces of HD sufferers. I would still be capable of grasping and expressing the poignancy of my situation. My suicide note would be pitched at posterity. I would administer a fatal dose of heroin and that would be that. The idea of going during the pre-symptomatic period had a lot to recommend it. I'd be able to "author" my death in the way I authored my wedding, ensuring that it was poetic and resonant. More importantly, I'd never be tempted to blog my descent into incoherence. Did the people journaling endlessly on all those HD websites never, I wondered, talk or think of anything else? Their devotion to their disease seemed drone-like, and I cleaved towards the pro-euthanasia lobby, sensing they were more my type.

Dominic Lawson has observed the right-to-die lobby comprises "powerful people" who are used to exerting control over their lives, and I suppose I thought of myself as one of them. I'd never had a normal job and found it hard to cope with people telling me what to do. My opinions were my own, developed without reference to God, convention or morality. I considered myself intellectually autonomous (as if such a thing were possible).

I identified heavily with the portrayal of PSP (progressive supranuclear palsy) sufferer Anne Turner in the BBC's well-intentioned drama A Short Stay In Switzerland, which tackled the increasingly fashionable theme of euthanasia. Confronted with her neurological malaise, Turner was steely and determined to enact the rationally arrived at decision to die: "You know what has to be done and you just do it."

Dynamic decision-makers such as Turner regard a loss of control over their lives as a fate worse than death. They perceive patient-hood as degrading. I perceived it as a form of oppression. HD seemed like the worst kind of corporate boss, defining my agenda and limiting my capacity for self-expression. Resisting gave me a buzz I hadn't felt since my youth. I was fighting for my rights!

Having regained control over her life by her decision to die, Turner becomes calm. I felt the same sense of inner peace, convinced I would be doing the right thing for my family. The film's deathbed scene at Dignitas showed the family grieving healthily. Experiencing closure, you sense they will recover quickly – and so it proves.

According to Derek Humphry, author of a seminal 1991 euthanasia textbook , "The closure in a case of accelerated, date-fixed dying is more effective and poignant because everybody concerned knows in advance that the patient will be gone at a pre-ordained time." I wanted to give my family the same gift.

Humphry also promised better days ahead. With the matter settled, I'd be free to make the most of the time remaining. But only if I laid my plans carefully. Meticulous forward planning was necessary for "self-deliverance with certainty".

With this in mind, I began composing a letter to my daughter. The act would be impossible to account for when there was nothing observably wrong. At risk herself (she cannot choose to take the test to see if she has inherited the gene until she turns 18), she would be terrified about what was to come. Rather than rush, I realised I'd have to wait until midway through the illness. It was important to write now, while I was still making sense. I meant to explain, but found myself arguing, as I had to my husband, in the manner of a sixth-form debater. My attempts to win her round to my way of thinking sounded smooth and self-justifying. Rhetoric crept in as I did my utmost to convince her that she would be OK without me.

With the escape hatch well in view, I started functioning more normally. At my instigation, we went on a series of memorable family days out. A trip on an open-topped bus to the Science Museum had a stagey quality, like the life-affirming montage in a film about someone with a terminal illness.

The next few weeks were spent adjudicating methods. Overdosing on heroin in the Chelsea hotel seemed hackneyed, on reflection.

The Dignitas route was expensive but effective. Three thousand pounds would buy three consultations and a lethal dose of the drug popularly considered to be the least physically and emotionally traumatic way to go. I guessed this was what Baroness Warnock and other proponents of assisted dying meant when they talked about "easeful death". In their accounts, suicide was a gorgeous Saturday morning lie-in, not a violent rupture.

The success rate was 100%, though it was clear that not everyone "went" at the same pace. The process took anything from 15 minutes to several hours to complete. I worried, as I had when giving birth, that something irritating in the attendant's manner might inhibit my natural processes. I wanted to vet them, but this wasn't possible – as with NHS midwives, you had to make do with whoever was on at the time.

I gave proper consideration to the DIY options. Their efficacy was harder to establish. Dr Philip Nitschke's handbook, a Which? of suicide methods, ranks methods numerically according to his Reliability & Peacefulness Test.

Top of the scale, at the time of writing, was a method devised by Nitschke himself in 2008. It sounded excellent, but potentially difficult for someone with HD. Midway through the illness, the chorea and lack of coordination would make anything requiring fine motor movements tricky to enact. There was one other problem. At the end, I wanted to look like myself, not like one of the diagrams in the book. I had the uneasy sense that following Nitschke's instructions to the letter would result in my death being an advert for Nitschke.

The head of Dignitas, Ludwig Minelli, is less a salesman than a philosopher, his enigmatic bearing more in keeping with his calling than with Nitschke's self-promotion. I'd enjoy chatting with him. In my fantasy, we'd be on cane chairs in his Zurich apartment discussing astronomy. I imagine him telling me that, in cosmological terms, my death at Dignitas would precede his by only a few milliseconds. He would congratulate me on my clear-sightedness.

Minelli doesn't believe in false consciousness. We are all competent and capable of deciding whether and when to avail ourselves of this "marvellous possibility". Everyone should have the right to kill themselves. For years, he has been demanding that the rules prohibiting the disabled and mentally ill from seeking an end be relaxed. To cope with the extra demand, Minelli envisages a Dignitas-style clinic on every street corner.

In 2008, 23-year-old Daniel James was paralysed in an accident on the rugby field. The dissonance between his self-image as a rugby hero and the reality of life as a tetraplegic proved fatal to his morale. His suicide at Dignitas was controversial, but his mother was sure she had done the right thing. In an interview afterwards, she said she was grateful to Dignitas for extending the suicide option to people without terminal illnesses.

The suicide doctor's smugness seems justified, reflecting increased consumer interest in "end of life solutions". It's no longer just bearded freethinkers or larger-than-life grandes dames engaging them, but dynamic decision-makers rejecting some second-rung, low-flying version of their being. For me, suicide was an act of self-preservation. I wanted Minelli to save me from the embarrassment of finding my self-image as a witty sophisticate no longer "matched" the reality. According to Wexler, the HD sense of humour, while robust, was infantile. From where I'm sitting, the prospect of spending Christmases laughing at Mr Bean feels like a fate worse than death. In my fantasy, Minelli offers to conduct my deliverance himself. It takes 10 minutes from beginning to The End.

Apart from my dad, I'd never seen anyone with HD. His affected relatives were all kept under wraps. I became fascinated by Wexler's report of a community of HD sufferers in Venezuela where, through an accident of history, HD has become endemic. Her account of the inhabitants of the fishing villages on the shores of Lake Maracaibo was shocking and compelling, and eventually I decided to go there myself. En route to Barranquitas, I worried my curiosity might prove ill-advised. An article in Business Week said the town was "like something out of the Twilight Zone".

On arrival, I was surprised how much of the scene was recognisable from Wexler's 20-year-old accounts. There was still no sanitation or running water. The shacks where most of the victims lived looked no more commodious. Here were the kids with their prematurely furrowed brows. And here was Lake Maracaibo, glinting ironically.

In one compound I was introduced to a family of eight. They described life with their HD-affected relative. For the past few years, Mariela had been aggressive, fighting her family and shouting at the kids. She was no longer herself, but a cipher of the illness. From her sister Marisela's account, it was clear she is in the later stages of what they call "el mal" – the evil. I was shocked to discover that she was seven months pregnant, but not surprised to learn that her symptoms worsened during pregnancy. I felt a stab of concern for her unborn child.

A local clinic offers sterilisation to patients with el mal. The doctor there says she has terrible trouble persuading women to have the operation. Mariela refused, even though she already had three children. How irresponsible, I thought.

According to her sister, Mariela often threatens to throw herself into the lake. Her raging seems to support the pro-suicide lobby's contention that life without self-determination is intolerable. The repulsive image of Mariela gasping for breath in the toxic waters of this polluted lake, as her body's reflexes conflict with her will, haunted me for weeks. I'm not sure how Nitschke would rate asphyxiation in this toxic soup. It would be reliable but less than peaceful. And yet how could she resist? It's a shorter trip than London to Zurich.

Marisela said that when she goes to work she worries about her sister. She described her relief, every time she comes home, on finding her alive. My expectation that I'd detect a note of ambivalence in the relief was misplaced. The trauma and tedium of life spent caring for this doppelganger is, for Marisela, preferable to the alternative. Whenever it happened, if it ever did, her sister's suicide would play as self-destruction rather than self-deliverance.

I had never thought of suicide as violent or vile, and no wonder – our preferred methods are designed to obscure this painful reality. Suicide consumers have been sold a chimera of a "peaceful" end. The suppression of our suffocation responses has made it possible for us to think of suicide as an idea rather than a physical process. I now see that suicide isn't a modest proposal but a very immodest one.

This realisation was most unwelcome, like finding out your lover's true nature. I was still in love with the idea of easeful death, and yet the knowledge – this dark apprehension of the truth – couldn't be put aside. It may have played a part in Mariela's unwillingness to carry out her threats, but it wasn't the whole story. With a sinking heart, I apprehended the rest.

"Does she still love her children?"

"Yes."

"Do they know it?"

"Yes." She gestured up towards a tree. "When she's swinging here in the hammock with the kids playing underneath, everything is OK."

One peculiarity of HD is that it leaves intact the sufferers' ability to love their family. This is both the best thing about the illness and the worst. It means sufferers are likely to choose life, with all that this implies – and explains why Mariela has chosen a decade of terrible suffering over death.

Maternal love pins Mariela to the shore, defiantly producing children. I no longer feel she is irresponsible to refuse sterilisation. Mariela is landlocked, I realise, and so am I. The lake's redemptive promise cannot be fulfilled. Suicide is a fantasy. Loving my daughter, I am doomed to live.

I almost cancelled the visit I had scheduled to the clinic of Casa Hogar, there on Lake Maracaibo. Set up by an inspirational Venezuelan doctor, Margot de Young, in 1999, this is a centre where those in the advanced stages of HD come to live out their last months or years. Committed to life now, I knew that this would be me one day, writhing and incontinent in some no-frills holding pen for the damned.

At first glance, my fears were confirmed. There were no eco-friendly sculptural installations, no activity room, no garden, no therapeutic zones painted in colours with a positive emotional impact. The tiles were an institutional blue. A plastic Virgin Mary gazed down from the cornices.

Nurse Erlinda Guerrero told me that she learned everything she knows about how to look after these "special patients" from the clinic's founder. An overwhelming level of need in these communities prompted Young to turn a former bar in a run-down part of the barrio St Luis into a clinic for HD sufferers. The building was cheap, but Casa Hogar's running costs are high. The nurse sounded anxious, conveying a sense of crisis. Food bills alone make it very expensive. The 34 inpatients consume vast quantities – as much as athletes, which in a sense they are. Chorea expends a lot of calories.

On the mezzanine level, we were introduced to a woman sewing straitjackets and bibs. She was wearing the carers' uniform – black trousers and a striking shirt in nursery print of a teddy bear hugging a rabbit. This struck me as rather un-PC. I'd heard that Venezuelans were sentimentalists, but still felt affronted on the patients' behalf. Were they too far gone to feel patronised by this depiction of them as flopsy bunnies?

Looking down at the scene below, I felt again that Minelli and the others are right. Without autonomy, life is meaningless.

The chairs were all facing a flickering telly. Their occupants all looked miserable. The lack of stimulation had clearly hastened the erosion of their pre-HD personalities. Without computers, they couldn't even blog. What would they have said if they could? There was no scene to record, none of the intrigues or dramas that make life interesting. It was terrible to think that some of them had been pitching on these same chairs for a decade, ever since the clinic opened. Helping them to die would surely be a more compassionate response to their plight than this perverse and costly commitment to keeping them alive.

"Aren't they bored?" I asked.

Nurse Guerrero looked offended. It took me a while, but then I saw why.

Lunch at Casa Hogar was one of the least boring I've ever attended. The atmosphere was charged with genuine jeopardy. Watching a patient being spoonfed, I was surprised to note that he didn't look passive or babyish. On the contrary, his face bore an expression of deep concentration, like a chess master between moves. He had more to lose than Kasparov, however.

Dysphagia – difficulty swallowing – is the most common cause of death in late-stage HD. The risk of choking means meal times contain the whole drama of human existence. Reaching for the spoon and risking death, the man revealed himself as a dynamic decision-maker of the first order.

When the bowl was empty, I wanted to applaud. I wanted him to live! This thought was interrupted by a wail of grief from the other side of the room. One of the most depressed-looking women, Luzmila, rose, lamenting, to her feet. Nurse Guerrero explained she'd recently found out that her son wouldn't be visiting at the weekend, as he'd promised. Nurse Guerrero hugged her consolingly. Her expression conveyed sympathy and maternal acceptance. Later she reminded me that most patients at this stage of the illness are aware of what they've lost. They are in mourning, and should be treated with the respect accorded to the bereaved. I understood why they are special. They are not in denial about their losses, like the rest of us.

The hug went on for a long time. A bit of me was willing her to do something, anything, to cheer the lady up. Her manner implied, riskily, that things are as bad as they appear.

It worked. Luzmila sat down, then got up again. She resumed lamenting in the same vein. Nurse Guerrero repeated the whole process with no trace of weariness. I felt I was witnessing a sacred ritual.

I, too, longed for a hug. One of the carers, Margarita Parra, obliged. In her arms, I feel like a rabbit being hugged by a teddy bear. I forget all my questions, which feels like a blessing.

Earlier in the day, Nurse Guerrero had told me I should listen to what people were saying, rather than assume I knew. I felt annoyed until I realised that that is what I had been doing with the patients, assuming their lives were meaningless. I'd been doing the same thing with myself, too, assuming I knew what I would want without listening. In Margarita's arms, I tuned into my being. I became aware of my self-consciousness about when would be the right time to pull away from the embrace, my anxiety about the photographer hovering nearby, my grief for the future, and my fear that I will end up like Luzmila, yearning for my children with no way of holding their attention.

Registering the discomfort of existence, I felt a great wave of self-pity, the first since my diagnosis. I felt worthy of being cherished and knew I'd do whatever it took to survive.

Back home, I told my husband he was right. The case for carrying on can't be argued. Suicide is rhetoric. Life is life.

• Samaritans provides confidential support, 24 hours a day, for people who are experiencing feelings of distress or despair, including those that could lead to suicide.

• Huntington's disease is an incurable hereditary disorder of the central nervous system. For more information on the disease, including treatments available for sufferers, as well as advice for families and friends, go to hda.org.uk

· This article was amended on Monday 8 February 2010 to remove personal details of one of the people featured.