"The really amazing thing, the extraordinary eye-opener that surprised the most optimistic of us, was the immediate and overwhelming success of the Pelicans." So wrote Allen Lane, founder of Penguin and architect of the paperback revolution, who had transformed the publishing world by selling quality books for the price of a packet of cigarettes. Millions of orange Penguins had already been bought when they were joined in 1937 by the pale blue non-fiction Pelicans. "Who would have imagined," he continued, "that, even at 6d, there was a thirsty public anxious to buy thousands of copies of books on science, sociology, economics, archaeology, astronomy and other equally serious subjects?"

His instinct was not only commercially astute but democratic. The launching of the Penguins and Pelicans ("Good books cheap") caused a huge fuss, and not simply among staid publishers: the masses were now able to buy not just pulp, but "improving", high-calibre books – whatever next! Lane and his defenders argued that owning such books should not be the preserve of the privileged class. He had no truck with those people "who despair at what they regard as the low level of people's intelligence".

Lane came up with the name – so the story goes – when he heard someone who wanted to buy a Penguin at a King's Cross station bookstall mistakenly ask for "one of those Pelican books". He acted fast to create a new imprint. The first Pelican was George Bernard Shaw's The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism, Capitalism, Sovietism and Fascism. "A sixpenny edition" of the book, the author modestly suggested, "would be the salvation of mankind." Such was the demand that booksellers had to travel to the Penguin stockroom in taxis and fill them up with copies before rushing back to their shops. It helped of course that this was a decade of national and world crisis. For Lane, the public "wanted a solid background to give some coherence to the newspaper's scintillating confusion of day-to-day events".

Shaw wasn't a one-off. The other books from the first months – written by, to name four of dozens, HG Wells, RH Tawney, Beatrice Webb, Eileen Power – were successful too. (This despite, or because of, the fact that the co-founding editor of the series, VK Krishna Menon, was a staunch socialist and teetotal vegetarian who drank 100 cups of tea a day and slept for only two hours a night.) The whole print order of Freud's Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Pelican No 24, sold out in the first week.

These books were like an education in paperback form – for pennies. The title of Virginia Woolf's The Common Reader, another early bird, was apposite (though it has since been misinterpreted as snooty): in the essays, Woolf attempted to see literature from the point of view of the non-expert, as part of what Hermione Lee has called her "life-long identification with the self-educated reader". It flew off the shelves.

Reading on a mobile? Click here

It was the beginning of an illustrious era. Nearly 3,000 Pelicans took flight during the following five decades, covering a huge range of subjects: many were specially commissioned, most were paperback versions of already published titles. They were crisply and brilliantly designed and fitted in a back pocket. And they sold, in total, an astonishing 250m copies. Editions of 50,000, even for not obvious bestsellers, were standard: a 1952 study of the Hittites – the ancient Anatolian people – quickly sold out and continued in print for many years. (These days a publisher would be delighted if such a book made it to 2,000.) The Greeks by HDF Kitto sold 1.3m copies; Facts from Figures, "a layman's introduction to statistics", sold 600,000. Many got to the few hundred thousand mark.

"The Pelican books bid fair," Lane wrote in 1938, "to become the true everyman's library of the 20th century … bringing the finest products of modern thought and art to the people." They pretty much succeeded. Some were, as their publisher admitted, "heavy going" and a few were rather esoteric (Hydroponics, anyone?). But in their heyday Pelicans hugely influenced the nation's intellectual culture: they comprised a kind of home university for an army of autodidacts, aspirant culture-vultures and social radicals.

In retrospect, the whole venture seems linked to a perception of social improvement and political possibility. Pelicans helped bring Labour to power in 1945, cornered the market in the new cultural studies, introduced millions to the ideas of anthropology and sociology, and provided much of the reading matter for the sexual and political upheavals of the late 60s and early 70s.

The film writer David Thomson, who worked as an editor at Penguin in the 60s, has recalled that as an employee "you could honestly believe you were doing the work of God … we were bringing education to the nation; we were the cool colours on the shelves of a generation." It was all to do "with that excited sense that the country might be changing".

Similarly, in Ian Dury's classic song, one of his "Reasons to be Cheerful" is "something nice to study", and his friend Humphrey Ocean has said the lyrics sum up "where he was at … The earnest young Dury – Pelican books, intelligent aunties, the welfare state, grammar school. It's nothing to do with rock'n'roll really, it's all to do with postwar England at a certain, incredibly positive, moment."

The leftish association with improvement – self and social – had always been part of the Pelicans. The wartime years were good ones for autodidacts. Orwell wrote that a "phenomenon of the war has been the enormous sale of Penguin Books, Pelican Books and other cheap editions, most of which would have been regarded by the general public as impossibly highbrow a few years back." One of the driving forces behind Pelican was the amiable, crumpled but well-connected WE Williams – "Pelican Bill" – an inspiring evangelist for the democratisation of British culture, who not only had ties to adult education (the WEA) but became director of the influential Army Bureau of Current Affairs, and during the war ensured the imprint thrived among servicemen. (Koestler called these self-improvers the "anxious corporals".) A 1940 book on town planning went through a quarter of a million copies. Richard Hoggart later wrote of his time in the forces that "We had a kind of code that if there was a Penguin or Pelican sticking out of the back trouser pocket of a battledress, you had a word with him because it meant he was one of the different ones … every week taught us something about what might happen in Britain."

After the war, as Penguin collector Steve Hare has recognised, the idea of a Pelican home university became more explicit; the number of "Pelican originals" increased, and the commissioning editors were astute in often choosing young scholars on the rise. (The books were also expertly edited, notably by the tattoo-covered Buddhist ASB Glover, a former prisoner with a photographic memory who had memorised the Encyclopedia Britannica behind bars.)

So if you wanted to find out about ethics or evolution or sailing or yoga or badgers or fish lore or Soviet Marxism, it was often a blue-spined paperback you cracked. The volumes came thick and fast, and were classy. In the 10 months between August 1958 and May 1959, for instance, Pelican titles included Kenneth Clark's study of Leonardo, Hoggart's The Uses of Literacy, The Exploration of Space by Arthur C Clarke, one of the studies in Boris Ford's highly influential and bestselling Pelican Guide to English Literature, A Land by Jacquetta Hawkes (described by Robert Macfarlane as "one of the defining British non-fiction books of the postwar decade") and A Shortened History of England by GM Trevelyan. And this selection is fairly typical.

Hoggart's book, one of the founding texts of cultural studies, which taught, among other things, that popular culture was to be taken seriously, was a good seller for Pelican: 33,000 in the first six months and then 20,000 copies a year through the 1960s. It has been suggested that one of the impulses behind Hoggart's criticism of commercialised mass culture was his sense that the opportunity to build on the autodidactic legacy of 1939-45 – the Pelican-style legacy, as it were – was at risk. But the imprint itself thrived, and published other books that were to become cultural studies classics: Michael Young's The Rise of the Meritocracy (No 485, September 1961), later misunderstood by Tony Blair, who didn't grasp that it was an argument against meritocracy – "education has put its seal of approval on a minority". Young, with Peter Willmott, also wrote the seminal Family and Kinship in East London, another Pelican, and at one time known affectionately by sociologists as "Fakinel", pronounced with a cockney accent. Raymond Williams's Culture and Society (No 520, March 1961) was another of the countless Pelicans at the centre of a revolution in thinking.

The books were also an important conduit of American intellectual life and progressive thought into Britain. The Sea Around Us by Rachel Carson, who had yet to write Silent Spring, had been an acclaimed bestseller in the US, and was published as a Pelican in 1956. JK Galbraith's The Affluent Society was published in 1962; Jane Jacobs's The Death and Life of Great American Cities came out in Britain three years later. Vance Packard's The Naked Society and The Hidden Persuaders questioned the American dream. Erving Goffman and Lewis Mumford appeared under the imprint, as did Studs Terkel's report from Chicago, Division Street: America.

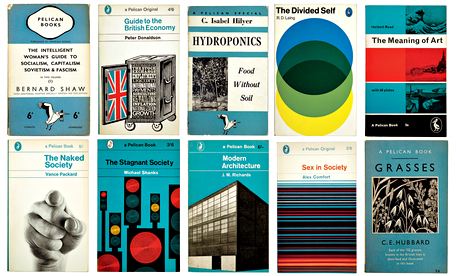

The fashionability of Pelicans, which lasted at least into the 70s, was connected to this breaking open of radical new ideas to public understanding – not in academic jargon but in clearly expressed prose. But it was also because they looked so good. The first Pelicans were, like the Penguins, beneficiaries of the 30s passion for design. They had the iconic triband covers conceived by Edward Young – in Lane's words, "a bright splash of fat colour" with a white band running horizontally across the centre for displaying author and title in Gill Sans. A pelican appeared flying on the cover and standing on the spine. After the war, Lane employed as a designer the incomparable Jan Tschichold, a one-time associate of the Bauhaus and known for his Weimar film posters. His Pelicans had a central white panel framed by a blue border containing the name of the imprint on each side.

In the 60s the books changed again, to the illustrative covers designed by Germano Facetti, art director from 1961 to 72. Facetti, a survivor of Mauthausen labour camp who had worked in Milan as a typographer and in Paris as an interior designer, transformed the Penguin image, as John Walsh has written, "from linear severity and puritanical simplicity into a series of pictorial coups". The 60s covers by Facetti (eg The Stagnant Society by Michael Shanks), and by the designers he took on – Jock Kennier (eg Alex Comfort's Sex in Society), Derek Birdsall (eg The Naked Society) – are ingenious, arresting invitations to a world of new thinking.

Jenny Diski has written of subscribing in the 60s to "the unofficial University of Pelican Books course", which was all about "gathering information and ideas about the world. Month by month, titles came out by Laing and Esterson, Willmott and Young, JK Galbraith, Maynard Smith, Martin Gardner, Richard Leakey, Margaret Mead; psychoanalysts, sociologists, economists, mathematicians, historians, physicists, biologists and literary critics, each offering their latest thinking for an unspecialised public, and the blue spines on the pile of books on the floor of the bedsit increased."

"If you weren't at university studying a particular discipline (and even if you were)," she goes on, "Pelican books were the way to get the gist of things, and education seemed like a capacious bag into which all manner of information was thrown, without the slightest concern about where it belonged in the taxonomy of knowledge. Anti-psychiatry, social welfare, economics, politics, the sexual behaviour of young Melanesians, the history of science, the anatomy of this, that and the other, the affluent, naked and stagnant society in which we found ourselves."

Pelicans reflected and fed the countercultural and politically radical 60s. Two books by Che Guevara were published; Stokely Carmichael's Black Power came out in 1969. Noam Chomsky and Frantz Fanon were both published in 1969-70. Martin Luther King's Chaos or Community? came out in 1969, as did Peter Laurie's Drugs. Peter Mayer's The Pacifist Conscience was published as LBJ escalated the Vietnam war. AS Neill wrote about his lawless progressive school Summerhill while Roger Lewis published a volume on the underground press.

In terms of history there was Christopher Hill on the English revolution and, to mark the 1,000th Pelican in 1968, EP Thompson's The Making of English Working Class, a book admirably suited to a left-leaning imprint flavoured by Nonconformist self-improvement. (The Guardian published a special supplement to celebrate the landmark.) In less than a decade it had gone through a further five reprints.

Owen Hatherley has described the Pelicans of the late 60s as "human emancipation through mass production … hot-off-the-press accounts of the 'new French revolution' would go alongside texts on scientific management, with Herbert Marcuse next to Fanon, next to AJP Taylor, and all of this conflicting and intoxicating information in a pocket-sized form, on cheap paper and with impeccably elegant modernist covers."

But then decline. The Pelican identity seems to have become diluted in the late 70s and 80s, and 25 years ago the last book appeared (The Nazi Seizure of Power by William Sheridan Allen, 1989, No 2,878). As an imprint it was officially discontinued in 1990. The reasons are murky. The Sunday Times suggested it was "for the most pedestrian of reasons: the name was already copyright in America and was not so well known in foreign markets". A Penguin spokesman also mentioned at the time that the Pelican logo gave the message: "this book is a bit worthy".

They were, perhaps, out of sync with the times. But they remained in second-hand shops. A splurge of Pelican blue on your shelves or in your pocket could still define the person you were, or wanted to be. I remember myself in my late teens, posing around with a copy of The Contemporary Cinema by Penelope Houston I had picked up on a stall for small change (it came out in 1963). I knew absolutely nothing about Antonioni and Bergman, Resnais and Truffaut, but I knew I should know about them, and I liked the imaginary version of me in a polo-neck, very fluent in such matters. Plus the cover was cool. I was a bit late to the party, but I was definitely a Pelican sort of person.

And now they are back, in a new series of originally commissioned books. The first volumes come out in May, and the opener (No 1) seems very Pelicanish: Economics: A User's Guide by the heterodox economist Ha-Joon Chang (whose 23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism was a bestseller); it is a "myth-busting introduction" written "for the general reader".

Also forthcoming are The Domesticated Brain by the psychologist Bruce Hood, Revolutionary Russia by Orlando Figes and Human Evolution by the anthropologist Robin Dunbar (who caused a splash in our Facebook age with How Many Friends Does One Person Need?). Non-fiction sales have been falling in recent years, and no doubt Penguin's aim is to capitalise on the now-fetishised Pelican brand. The new books will be turned out in a shade of the famous pale-blue livery and the Pelican logo itself has been updated for the relaunch. Given the lucrative nostalgia market in Penguin mugs, postcards and tea-towels – not to mention a roaring collectors' trade and art-world homages such as Harland Miller's beaten-up paintings – the publishers can hardly be unconscious of the importance of design.

And, as with Allen Lane in the 1930s, there is more to the relaunch than financial opportunism. Penguin seems sure that the self-education urge is still strong. Hood has himself pointed out that while university education is, unlike in Lane's day, open to many (at least for the time being), it has become more utilitarian: a more rounded education has, more often than ever, to happen around the edges. Wikipedia, however excellent, isn't enough.

According to Penguin the hope is that readers will once again "turn to Pelicans for whatever subjects they are interested in, yet feel ignorant about – Pelicans can be their guides". It's the latest incarnation of the unofficial university, and of the optimistic belief in the appeal and influence – and profitability – of "Good books cheap".

Ten Pelican highlights

1. Psychopathology of Everyday Life by Sigmund Freud (Pelican in 1938)

Perhaps Freud's most popular book, this is a study in part of everyday "faulty actions" – such as forgetting names – that illuminate the workings of the unconscious.

2. The Common Reader by Virginia Woolf (1938)

A collection of essays on literary subjects. The "common reader … differs from the critic and the scholar … He reads for his own pleasure rather than to impart knowledge." The Second Common Reader soon followed.

3. An Outline of European Architecture by Nikolaus Pevsner (1943)

Pevsner was one of Allen Lane's best signings (the publisher gave the green light to The Buildings of England series). Pevsner was responsible for the magisterial Pelican History of Art series; An Outline sold half a million copies.

4. Coming of Age in Samoa by Margaret Mead (1944)

A classic study by (at the time) the world's most famous anthropologist focusing largely on adolescent girls. The directions of its influence were varied but by taking in attitudes towards sex in traditional cultures, Mead's work later informed the 60s sexual revolution.

5. The Pelican Guide to English Literature, edited by Boris Ford (from 1954)

Ford was a Leavisite, but Leavis apparently wasn't best pleased with this spreading of the word to the masses (contributors included TS Eliot, Lionel Trilling and Geoffrey Grigson). But it was a great if always controversial success. One volume, The Age of Chaucer, alone sold 560,000 copies.

6. The Uses of Literacy by Richard Hoggart (1958)

The text on the original Pelican cover reads: "A vivid and detached analysis of the assumptions, attitudes and morals of working-class people in northern England, and the way in which magazines, films and other mass media are likely to influence them."

7. The Affluent Society by JK Galbraith (1962)

A powerful, bestselling argument for the need to invest in public wealth.

8. The Divided Self by RD Laing (1965)

Pelican's books on psychology and psychiatry (by Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Anthony Storr, Charles Rycroft, DW Winnicott) were the inspiration for many British practitioners to enter the field of mental health. Laing's anti-psychiatry book, which argued that schizophrenia is a social rather than medical condition, attracted cult-like devotion from famous hippy admirers.

9. The Making of the English Working Class by EP Thompson (1968)

The 1,000th Pelican, and a runaway commercial and critical success. History was one of the strongest areas for the imprint: other authors included AJP Taylor, Asa Briggs and Eric Hobsbawm. GM Trevelyan's Whiggish Pelican History of England shaped the historical thinking of generations.

10. Ways of Seeing by John Berger (1972)

Art books were also central to Penguin. Robert Hughes, newly settled in London, published a Pelican original (The Art of Australia) in 1966. But perhaps the most renowned art Pelican was this book by John Berger, a printed version of his TV blast against Kenneth Clark, in which he argued for a political reading of art. The volume was innovatively and expertly designed by Richard Hollis; the essay text begins on the cover, and illustrations are embedded on the page next to the relevant text. It changed the art world.