Here’s the thing: the majority of Americans are fat. So much so that most people don’t even consider themselves fat, probably because everyone around them is also fat. Lots of kids are fat too – a trend I’ve really started to notice since becoming a father two years ago. Toddlers and babies are so fat that sometimes I worry that my own son, Ayhan, looks malnourished.

But my son isn’t malnourished. In fact he’s strong and lean, and acts like one of the healthy monkeys in the ongoing Wisconsin National Primate Research Center caloric restriction study: perky, energetic, and excited about eating proffered bits of fruit. So when I step back and get a bit of perspective, I’m not worried.

I’m more concerned about how children are being set upon an unhealthy dietary path that starts not just when they’re born, but when they’re conceived. Recent studies find that what mothers eat while pregnant shapes children’s palates in vitro. So if mama is regularly indulging in ice cream and salty snacks, baby may be predisposed to crave those too.

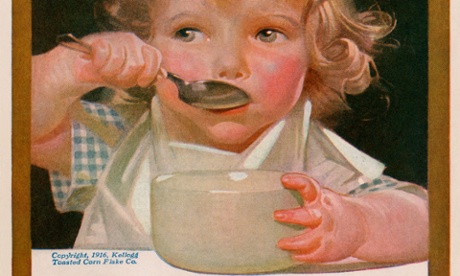

Then when they’re born, too many children are raised on baby formula, which is far less healthy than breast milk (a topic I already discussed, to much maternal anger). At around six months, when starting on solids, many parents lead their children down another wrong path – that of powdered cereals, premade baby foods, and junk foods disguised as baby-friendly snacks. No wonder childhood obesity is at 17.3% in the US.

One recommendation: make your own baby food. I’m sure some readers will comment that cooking for baby is too much work. I’ll admit it takes some additional time – and in cities like Washington DC, where food is expensive, it’s not even necessarily cheaper than buying baby food in bulk online (even ignoring the labor costs). But homemade food is healthier, more sustainable and more real. I want my son to interact with real food, to know what he’s eating and to experience a variety of tastes and textures, something impossible when sucking food out of a foil pouch – the trendy new packaging for upscale baby food.

The good news is that some parents are indeed starting to make food – to the point where baby food companies are getting nervous and are innovating new healthier, fancier product lines. But I’m not sure the cook-your-own-baby-food trend will be enough of a step forward. Because even worse than premade baby food is the perniciousness of the Goldfish and other empty calories on playgrounds and stroller snack trays today.

Why would parents give salty, bright-orange fish-shaped crackers to their children? I still haven’t figured it out. In fact, I don’t know why they’d give any junk food at all to their toddlers. My wife and I haven’t exposed our son to any sweets, junk food or candy in his first two years (ok, he had maple syrup a few times when he ate pancakes off my plate instead of his own). We also haven’t given him any liquids but water and teas, and I believe our lives as parents have been radically easier because of this. No battles over juice, ice cream, muffins or cookies. In fact, the only reason our son knows the word cookie is because his aunt gave him a used copy of If You Give a Mouse a Cookie, a cute kids' book that is fun even without a full understanding of what a cookie is. Instead of junk, Ayhan eats food – real food that keeps him active and satiated and healthy.

What does this all mean for business? I wish I could say the majority of consumers will rebel against premade baby foods and marketed-to-baby junk foods, but that’s highly unlikely, as most new parents are too embedded in dominant consumer cultural norms to go down such a non-traditional path (especially when walking down that path takes a lot more work). So if companies make healthier baby foods, using better ingredients like quinoa and kale, and put them in fancier packaging, they’ll probably be able to sell it, and at a premium.

But there could well be an opportunity for farmers and produce vendors to profit off the new health consciousness of elite consumers and accelerate their transition away from premade baby foods. Whole Foods Market and farmers markets, for example, could show their customers how easy it is to bake sweet potatoes, mash them with a bit of butter, and put them in ice cube trays to freeze (ready to microwave with a few cubes of pureed peas and carrots when baby is hungry).

The 2010 baby carrots marketing campaign was an attempt to capture the savvy of junk food marketing and apply it to carrots to get kids to “eat ‘em like junk food.” But it was a flash in the pan attempt – $25m squandered with few long-lasting results. Better would be to build a longer-lasting marketing and outreach strategy to educate new parents about the best nutrition habits, such as breast feeding, then adding in real and healthy foods at about six months, with no added sugars or liquids other than water and breast milk. And if produce companies or grocery stores help demonstrate how that can be easier than – or at least as easy as – buying jars, perhaps more parents will take that path and create new profit opportunities for farmers and upscale markets.

And most importantly, when toddlers move beyond baby food, they’ll have no problem eating complex healthy foods, rather than subsisting off Cheerios and mac and cheese. Of course, along with processed food companies, medical and pharmaceutical industries won’t like that shift: there would be fewer symptoms to treat in a population not suffering from epidemic rates of diabetes and heart disease. But children, families and societies would certainly be far better off.

The sustainable living hub is funded by Unilever. All content is editorially independent except for pieces labelled advertisement feature. Find out more here.