As we switchback up the mountain roads, Lianne confides that she's scared of heights. I can't help feeling that it's brave of her to volunteer for a day on the Via Ferrata. An hour later, as I muster the courage to pull myself up some iron loops overhanging a drop of several hundred feet, I feel it's extremely brave of her, and perhaps a little bit brave of me.

Our Alpine guide, Pierrot, hangs nonchalantly on one arm and goads me verbally, "Are you going up, or what?" I go up, clear the bulge in the rock, and feel my hands shake with adrenaline as I clip myself onto the next section of steel cable.

I've done rock climbing in the classic British style, led by a more experienced climber who held the rope while I climbed. Via Ferrata is safer than that, and requires less skill. Not only am I firmly attached to a steel cable running the length of the route, most of the time I am clambering up steel rungs, not searching for crannies in the rockface in which to wedge boots or fingers.

But don't think this is better for someone scared of heights. In many ways, it's worse, as placing each hand and foot does not require every ounce of concentration. Scrambling monkeywise up alternating iron loops leaves plenty of brain free to contemplate the precipitous view and the birds circling below. I generally like heights, and I'm finding this a challenge. I'm glad I can't see Lianne's face.

The Italian Alps were first rigged with safety cables and footholds in the first world war, to help soldiers move around. Now Via Ferrata has spread throughout the Alps as a popular tourist activity, and I've come to the Mercantour National Park in France to try the route that Pierrot and his mates rigged at La Colmiane.

Mercantour is on the cusp of the Alps and the Côte d'Azur. On an autumn day the sun is hot but the breezes chilly. Mountain leader Mel Jones of Spacebetween discovered the area only a few years ago and, out of season at least, it's astonishingly deserted. In three days walking and clambering, I see more birds than people.

There's something to do all year round here, from snowshoeing to mountain biking. I'd like to blame the altitude, but for an unfit townie like me even a gentle stroll up the Val de Fenestre is exercise. I see my first chamois, posing on a slab of a rock, elegant deer-like silhouette against the sky. Across the valley brown cattle browse between boulders, their bells clanging like a chaotic gamelan. That, and the stream rushing down the valley floor, are the only sounds.

St Martin-Vésubie is a typical mountain town, steep pitched roofs readied against the winter, but its buildings hint at a grander past. It was once a major hub on the Salt Route. Salt travelled from Nice up the Var and Vésubie valleys to be stored here until the snow cleared from the passes to Italy.

A little way down the Vésubie valley, Lantosque is completely different. Perched on a promontory between two canyons, its ochre walls and terracotta tiled roofs declare it to be Provençale to the rock. Via Ferrata routes run along the smooth limestone walls of the canyons, only yards above the river: not exposed, like the mountain routes, but with the threat of a chilly dip only a steel cable away. These routes are only open at weekends outside the summer season.

Back at La Colmiane, we devour local bread, cheese and salami and smell the pines and Alpine herbs. I look down on the delicate wire-and-wood bridge that felt so high up when we crossed it this morning. Via Ferrata certainly does its job of moving inexperienced people up a mountain very quickly. Pierrot snores on the sharp stones, a feat almost as impressive as the Via Ferrata itself.

Lianne takes the footpath back to civilisation, saying it wasn't quite what she was expecting. She made the right decision. The next section requires what mountaineers call "exposed moves" - not hard, but involving the most undignified spread-eagled position, looking down at nothing but air and some shale a very long way below. Oh, and if you do miss your footing you face a 20-foot slide down the rockface before coming to rest, dangling in your harness. A mistake in Via Ferrata is very unlikely to kill you, but you could pick up some nasty scrapes or a broken ankle as you career towards the next fixing point of the cable.

We all become very handy with the clipping-unclipping routine. My climbing harness is attached to the mountain by two short lengths of sling, each with a metal carabiner that slides along the steel cable. Whenever I reach one of the hefty steel fixings drilled into the rock, I unclip one carabiner and reclip on the other side. Then I repeat the same with the other carabiner, leaving me free to work my way along to the next fixing point. The idea is that I can never fall off.

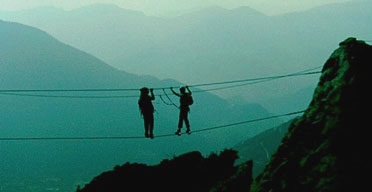

I accept this idea in theory, but there are still times when my rational mind has a hard job to persuade my hands and feet. Near the peak we reach a "monkey bridge", whose playful name belies the terrifying reality. It's three steel cables stretched across a void. You clip onto one, hold the second and walk across the third. That's right, it's tightrope walking with a safety line and a handrail.

I'm appalled to find I'm the only person willing to cross this. Mel, who has climbed mountains for 30 years, chooses the low road, followed (understandably) by partner Liz. Pierrot has volunteered to take a picture of me, so I bravely clip myself on and take the first steps alone, turning round to look at the rockface instead of the vast empty valley below. I'm trying not to remember my dream of the night before, in which a tightrope walker plummeted from his wire into a wedding party.

Unfortunately, four steps onto the bridge I realise that turning round has entangled my slings around the hand wire. Already taut, they certainly won't let me cross even halfway. Cursing myself, I return to the solid rock to sort them out, where of course they follow the golden rule that any task becomes harder in direct proportion to the height at which you're attempting it, due to fear, not altitude.

At this point, Pierrot shouts that the camera isn't working. I'm sorry to reveal that I'm shallow enough to regard this as justification to abandon the monkey bridge. If no proof of my bravery will ever exist, it seems a waste of a lot of nerve. I am 10 yards away from that bridge in no time at all and would even now be kicking myself for my cowardice were it not for Pierrot, who in a split second has delegated the camera, grabbed me by the harness and dragged me back to the bridge.

Forcibly clipped onto the safety line, and followed closely by a reassuringly hefty Alpine guide, I make my way gingerly out over an awful lot of nothing. It is a great view, but I'm not enjoying it as much as I might. When Pierrot offers to move away from me to improve the photo I squeak "No!" in my best French. Never believe anyone who tells you that Via Ferrata is a softy thing for tourists, like a theme park. By the time I put a grateful foot onto solid rock again, even I can smell my fear.

Six hours after the start we reach the top of Baus de la Frema. I'm wearier than I've been for years, but I feel fantastic. We're 2,246 meters above sea level, and through the haze I can see well into the Italian Alps. I don't even mind that it's a good hour's walk back to the car park. All I'm thinking about now is that first cold beer.

Way to go

Timandra tried the Mercantour Via Ferrata as a guest of Spacebetween. Contact Mel Jones or Liz Lord on 0870 243 0667

Spacebetween, La Zourcière, Quartier de la Brasque, Berthemont les Bains, 06450 Roquebilliere, France, Tel/Fax: +33 (0) 4 9303 4857

· Timandra flew to Nice with EasyJet (08717 500100). EasyJet flies to Nice from Gatwick, Luton and Stansted from £33.63 return including tax.