A woman stands outside the gates of the Harwoods adventure playground in Watford. It is cold and dark, and she is holding her two children's schoolbags. Harwoods is one of two playgrounds in the town that recently changed their policy on accompanied children; now parents must wait outside to collect them. "It is a shame," says the woman, who doesn't want to give her name. "I still don't really understand why they have done it. Now, you can't watch your child play, you don't know who is in there with your child, you don't know if there is bullying going on. It's nice to be able to see your children play with other kids, and now we can't."

The reaction of the national press was rather less measured: "Now parents banned from play areas . . . in case they're perverts," boomed the Express. "Prove you're not a paedo or you can't watch your own kids in playground," screamed the Sun.

Health and safety, usually appended with "gone mad", is a mainstay of rightwing columnists. Rarely a week goes by without Richard Littlejohn, in the Daily Mail, frothing over some new indignation – so much so that readers send him their own examples for him to get upset about. But earlier this month, David Cameron made an appeal to this strand of "nanny state" outrage in a speech attacking Labour's "over-the-top" approach to health and safety, which, he said, had created a "stultifying blanket of bureaucracy, suspicion and fear". He announced a Tory review of the legislation.

Back in Watford, Dorothy Thornhill, the mayor and council leader who was responsible for the adventure playground ruling, says she understands why some parents are upset, but that the press got the story wrong. "The way it was reported made it look as if we were banning parents from traditional playgrounds with swings," she says. "I think we were called jobsworths and it was all about how health and safety was taking over. From the newspaper reports, the public were quite right to feel this was a nonsense."

In fact, these are adventure playgrounds and recreation centres, she explains, which are supervised by trained staff who operate as childcare providers. "We have 400 parents who are very happy to leave their children there, and a few parents who wanted to stay." She says the staff who ran the centre felt that those parents could be a distraction. "The policy allows staff to concentrate on the children, not on what the parents are doing with their own children and with other children. It operates as a drop-off facility, and it becomes a different place if parents come." But the council is reviewing the situation, says Thornhill, "to see if that is what people want. Do they want childcare, or do they want somewhere to go with their kids?"

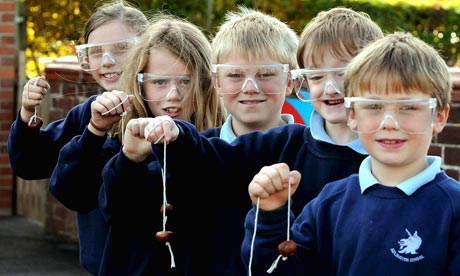

In the last few months, there have been countless stories of legislation and guidelines encroaching on our children's lives. There were the two police officers, Leanne Shepherd and Lucy Jarrett, who were told they weren't allowed to look after each other's children without an Ofsted inspection, since they were considered illegal childminders. At Adlington primary school in Macclesfield, children were told to wear goggles while playing conkers – Polly Broadhurst, the headteacher, appears so stung by the criticism that she refuses to talk to me, saying simply that the story was blown up out of proportion and that she cared only about the safety of her pupils.

In the Wiltshire village of Maiden Bradley, kite-flying has been banned from the park after inspectors from the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (Rospa) said that kites could become tangled in the overhead telephone cables and children could hurt themselves if they tried to climb the poles to free them. The swings in the playground have been allowed to remain, meanwhile, but only on condition that local councillors inspect the nuts and bolts every week.

And earlier in the year, a school in Biggleswade in Bedfordshire reportedly banned parents from attending sports day in case some of them happened to be paedophiles. Paul Blunt, from the East Bedfordshire Schools Sports Partnership, was quoted as saying: "All unsupervised adults must be kept away from children. An unsavoury character could have come in, and we just can't put the children in the event or the students at the host school at risk like that."

Once again, Blunt tells me the story was mis-reported, and that he would like to put the record straight, but has to be cleared by East Bedfordshire council before he can speak to me. The council says only that "the Partnership welcomes and encourages parents and spectators to attend. However, on this occasion, the facilities and resources were insufficient to accommodate the potentially large numbers of spectators without compromising the day-to-day running of a school."

Meanwhile, a survey of 490 teachers this summer by the digital channel Teachers TV threw up yet more tales of extreme health-and-safety guidance: a five-page guide on how to use glue sticks; children being made to wear goggles when using Blu-Tack; a ban on running in playgrounds. Others reported three-legged races being considered too dangerous for school sports days, and PE lessons being cancelled because the grass was wet.

Where do all these rules and regulations come from? Judith Hackitt, chief executive of the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), sighs when I mention the conker story. "We often read in the papers about 'health and safety gone mad', when no legislation exists to ban conkers, or make children wear goggles when using Blu-Tack," she says. "I think we're wrongly blamed for a lot of these stories. In reality, we become a convenient excuse to hide behind."

The HSE, she points out, is there to ensure employers protect employees at work, not to ensure that every aspect of our lives is risk-free (the HSE site has a "mythbusters" section that Cameron might have done well to look at before his speech: December's myth is that under health and safety "rules", actors in a panto can't throw sweets out to the audience).

If individual schools, councils and pantomime producers enforce their own health and safety rules, it is often "an overinterpretation of the regulations", says Hackitt. The Labour government has brought in a large number of regulations since 1997, as Cameron said in his speech, but these include the control of asbestos and lead, regulation of noise levels at work and the import and export of dangerous chemicals.

"Not exactly trivial things," says a spokesman from the Institution of Occupational Health and Safety, the professional association for the people who enforce the Health and Safety at Work Act. "We get such an unfair treatment, particularly from the more reactionary press." Hysterical media reporting, he says, has helped to create a culture of blame and compensation. "You get insurance companies putting up premiums and people either not wanting, or not being able, to run events properly – so blaming health and safety becomes an excuse."

Many stories can be dismissed as myths, but the moves to safeguard children have taken a couple of serious turns. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence is developing guidance that could see inspectors from local councils going in to homes where there are children under the age of 15, to check that there is sufficient safety equipment, such as smoke and carbon monoxide alarms, stairgates, hot-water temperature restrictors and oven-door guards. The inspectors are being instructed to focus on disadvantaged and low-income households.

"Children from low-income households are 13 times more likely to die from an accident in the home," says a spokesman. "We don't feel it is an unnecessary invasion of privacy. We're putting forward measures that could save people's lives."

Next year, an estimated nine million people will have to apply to the Independent Safeguarding Authority (ISA) to be told whether or not they are safe to be around children. This body was set up in the wake of the Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act in 2006, which arose from the inquiry into the murders of Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman in Soham by Ian Huntley. Huntley had been known to Humberside police and social services after allegations of sexual offences, but this information didn't come up during vetting procedures when Huntley became a college caretaker.

The ISA has already started vetting people who have been referred by employers with suspicions about their behaviour, and has placed some of them on its barred list. But from July next year, anybody who has contact with children (or vulnerable adults) once a week or more – including someone who volunteers with a children's group, and a parent who takes their turn ferrying other people's children to football matches – will have to be cleared by the ISA.

It will look at criminal convictions, but could also take into account "evidence" from employers or members of the public about an individual's lifestyle. Seven headteachers' groups have written to Ed Balls, secretary of state for children, schools and families, about their concerns that "disproportionate" bureaucracy is "strangling school life".

Professor Frank Furedi, the sociologist and author of Paranoid Parenting, describes these creeping measures as "the child protection industry". At best, it means sandpits disappearing from park playgrounds because of fears that they are harmful to children; at worst, it means treating every adult as a potential paedophile. A report produced in 2006 by the Manifesto Club, a group that campaigns against what it calls "hyperregulation" by the state, told of how volunteers at one children's Christmas party in Bristol had to wear colour-coded T-shirts – those who had been checked by the Criminal Records Bureau wore maroon ones, those who hadn't wore white. Volunteers were not allowed to be alone with a child, even to take them to the loo, and there were guards on the toilet doors to ensure this didn't happen.

A kind of stand-off of suspicion is being created. Adults don't trust children not to make allegations against them; children are being taught that adults are not to be trusted.

"All of this has a number of negative effects," says Furedi. "It normalises a 'worst-case scenario' way of thinking about everything. Children need a relatively positive attitude to the unknown, rather than being constantly protected from it. A lot of kids don't experience autonomy and independence. When everything comes with a health warning, you don't learn to manage risk."

What is the effect on them as they grow into adults? "When you diminish their aspiration for independence, we infantilise them. As a little experiment, I always ask my first-year students how they refer to themselves. Twenty years ago, they would consider themselves to be young men and women. Now they call themselves boys and girls. We are extending their childishness."

Furthermore, Furedi says that children aren't as innocent as we might like to think. "This does have an effect on their play. When I was a child, we used to call adults 'idiots' or similar. Now, I hear children refer to adults as 'paedo'. It's a joke, but all it needs is for one overzealous adult to overhear and start asking questions and somebody's life could be ruined. But these are the attitudes that we are communicating to children." And one that could have far more serious consequences for society than whether or not children get to play conkers without goggles.