Cancer leaves many scars. For survivors, the wounds that run deepest are often those left on the mind. Fear, anxiety and depression are common during recovery. But instead of popping a pill, could practising a few minutes of mindfulness a day be as effective as any drug?

While Buddhists have been practising the meditation technique for more than 2,000 years, medical science is finally beginning to catch up, discovering the extent to which focusing the mind on the present moment can help treat a range of mental conditions associated with cancer recovery.

In the largest trial to date, published last year in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, breast cancer survivors who practised mindfulness were found to have increased calm and wellbeing, better sleep and less physical pain. Clinical trials by Oxford University have shown that mindfulness is as effective as antidepressants, and in patients with multiple episodes of depression can reduce the recurrence rate by 40-50% compared with usual care.

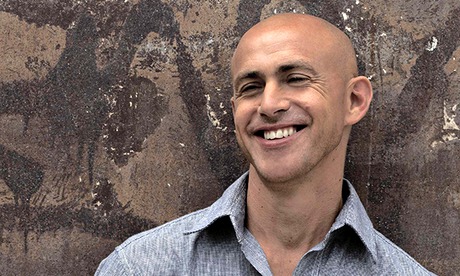

Andy Puddicombe's 20 years of practice were put to the test when he was diagnosed with testicular cancer last April. While the mindfulness expert and former Tibetan Buddhist monk expected the physical pain after surgery to remove his right testicle, he was surprised by the emotional and mental impact of recovery.

"The biggest shock about recovery is that there is no end point," he says. "People often talk about having beaten cancer, but I find that hard to relate to. I would say that nature has simply taken its course and I am very fortunate that it didn't spread."

Puddicombe, who aims to demystify meditation with his Headspace app, explains that mindfulness allows us to step back from our thoughts and feelings and view them with a different perspective. It would be very easy, he adds, to get caught up in negative thinking or feelings of anxiety and depression. But mindfulness gave him enough space to be able to embrace these emotions without getting lost in them.

"Rather than it being a terrible experience, it became a transformative one," he reveals. "It may sound a bit fluffy, but the reality is anything but. In fact, it was life-changing."

Psychotherapist Elana Rosenbaum has been practising and teaching mindfulness stress reduction techniques since the early 1980s. She believes her ability to focus the mind on the present moment and break patterns of negative thought helped her survive an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma which required bone marrow transplant surgery to remove.

She explains that recovering from cancer was a frightening experience. Once she had finished her treatment, she felt lost without the help and support of medical staff. Mindfulness helped her to face those fears.

Rosenbaum, who helps others use mindfulness in cancer recovery at the University of Massachusetts medical school, says: "People think you are the same. They think you have gone back to what used to be normal. But you're really different. It's a new normal and you don't know what that is. I have had several recurrences of the cancer and I live with uncertainty, but it's not my focus. Mindfulness helps me to value this moment."

Nice, the UK's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, approved a technique developed by Cambridge and Toronto Universities for the management of depression in 2004, which means the therapy is already available on the NHS.

Headspace's chief medical officer, Dr David Cox, prescribes cancer recoverers a dose of 10 to 40 minutes mindfulness practice a day. But once you are proficient at that, you have to remember to be mindful in anything and everything you do as much as possible, whether that's walking the dog or washing the dishes.

He believes the link between mind and body has been neglected for far too long and it is a breath of fresh air for many doctors that someone is finally asking the question. Cox says medical professionals have known about the benefits for a while and mindfulness offers a "glimmer of hope" for tackling the spiralling cost of healthcare on the NHS. Because sufferers of depression tend to be more apathetic about looking after themselves and taking medication, compliance with treatment is therefore worse.

One of the reasons that mindfulness is really catching on is that it can be delivered in a way that is entirely secular, stripped of any religious connotations, making it entirely acceptable to the wider population.

"Around 30 years ago, yoga was probably sniffed at a little bit and now it's much more mainstream," Cox adds. "To me, it's the perfect storm for something that can really help a vast number of people. I hope in five years' time it will have the same level of acceptance as brushing your teeth every day, eating your five a day and doing 30 minutes' exercise."