William Halsted, a pioneering New York surgeon with a cocaine habit gained from experimenting on himself to work out its anaesthetic properties, took his curative scalpel to the chests of his breast cancer patients with such crusading zeal that they were permanently disfigured, their shoulders in a state of collapse and arm movement compromised.

He scorned the "mistaken kindness" of others in his profession and hacked out muscles and bones alike, determined to excavate to the very roots of cancer. Once, in the 1890s, he described a patient as "a young lady whom I was loathe to disfigure". Somehow, you are certain he conquered this shameful moment of weakness.

He was a medical celebrity of his day, to whose operating theatre women with breast cancer beat a path of pilgrimage, and his name endures in the "Halsted mastectomy" – the radical removal of breast and surrounding tissue and lymph nodes that was still practised until just a few decades ago. If we have come far, it is in an extraordinarily short space of time.

The Emperor of All Maladies, Siddhartha Mukherjee's masterly "biography of cancer", is peopled with many such fearsome figures, from the paternalistic, God-like physician stalking the wards to the introverted loner in the lab. But without them, where would we be now? Mukherjee, himself "a lab rat", albeit one with a Renaissance fascination for literary quotations and analogies, pays homage to the dedicated and obsessive men who preceded him (barely a woman among them apart from Marie Curie and the entrepreneurial socialite Mary Lasker, whose campaigning strategy was crucial in obtaining US federal funds for the cancer fight).

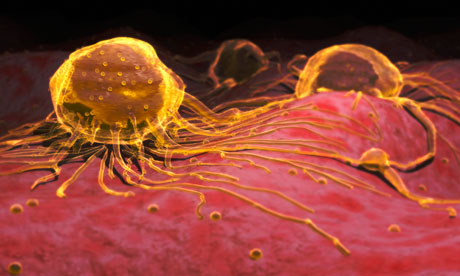

Just as you feel Mukherjee has affection even for the coldest and most arrogant of the cancer pioneers, so you sense his fascination with the dreaded disease itself. While his concern for his patients – and in particular Carla, whose leukaemia becomes one of the central motifs of the book – is real and feelingly described, it takes second place to his fascination with the behaviour of the cancer, which "explodes" out of their cells, and to the cat and mouse game that science has had to play to try to find ways to stop it in its tracks. Perhaps it is his own feeling for the disease that makes this Pulitzer prize-winning book so readable – at the same time an encyclopedic history of scientific progress against history and ripping yarn.