A vaccine against the highly infectious winter vomiting bug that strikes thousands of people in Britain each year is close to being tested in humans.

Doctors have approached government funders to begin human trials after laboratory tests showed the vaccine could prevent people from succumbing to the infection.

Researchers said the technical issues in formulating the vaccine appeared to be solved, and that regulators now had to assess the treatment's suitability for full-scale clinical trials.

The stomach bug, caused by seasonal norovirus, spreads rapidly between people and is difficult to kill off by cleaning. It has ruined countless holiday cruises, closed hundreds of hospital wards and torn through prisons.

In recent weeks, three US cruise ships have been forced to return early to their ports for deep cleaning after outbreaks of norovirus saw hundreds of passengers and crew struck down with diarrhoea and vomiting. Cruise ships are required to report norovirus outbreaks to the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention when 3% or more of those onboard go down with the bug.

"When it hits in a situation like a cruise ship, it spreads like wildfire," said Charles Arntzen, co-director of the Centre for Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology at Arizona State University.

Laboratories in England and Wales have confirmed more than 1,100 cases of norovirus in the first four weeks of 2012, according to figures from the Health Protection Agency. So far in this winter season there have been 755 outbreaks in English and Welsh hospitals, leading to 520 ward closures or restrictions on admissions.

Though the illness is generally mild and clears up in two to three days, people can remain infectious for more than three weeks. Most people who are fit and healthy make a full recovery.

"You can have diarrhoea and wash your hands thoroughly afterwards, but if you leave as few as 10 viruses on a door knob, and someone else picks it up, they can get the disease and spread it," Arntzen said. Since the 1980s, a second, more virulent strain of norovirus has emerged and now accounts for around 85% of outbreaks.

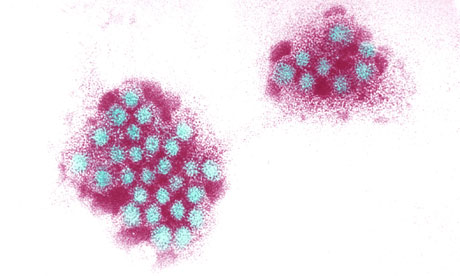

To develop the vaccine, scientists working with Arntzen took a gene from norovirus that codes for its protective protein coat and added it to a common tobacco virus. When the virus infected tobacco plants and multiplied inside their cells, it produced thousands of copies of the norovirus protein, which coalesced into virus-like particles. The particles are harmless, but can be used in a vaccine to trigger an immune attack on the virus.

Arntzen's group has teamed up with a group in Kentucky that grows tobacco plants on an industrial scale to manufacture the vaccine. From 1kg of tobacco plant, the researchers can make 10,000 doses of vaccine.

Lab tests of the vaccine showed it was most effective when given as a nasal spray, combined with a dried aloe extract, which made the vaccine stick to mucous membranes in the nose. Vaccine that contained aloe stayed in the nose for around three hours, which is long enough to prime immune defences in other mucous membranes around the body including the gut, where the norovirus strikes.

The results were presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Vancouver.

The final version of the vaccine is likely to carry virus-like particles from both major strains of norovirus, and possibly some common sub-strains, to ensure it provides broad protection against the bug. A single shot of nasal spray could be effective for six months to two years, Arntzen said.

The vaccine, which could be available in four to five years, may prove popular in children's day care centres and among cruise ship workers, hospital staff, carers in old people's homes, and the military, all of which face regular outbreaks of norovirus.