It began in the departure lounge at Stansted airport. John Suchet's wife, Bonnie, went to the lavatory and did not reappear for an unusually long time. Then came the announcement: "Would Mr John Suchet please come to the information desk?" When Bonnie saw him, she was relieved: "I thought I had lost you!" she said.

It was a faintly troubling incident – but airports are disorientating places. Suchet put it to the back of his mind. What neither of them knew then was that Bonnie was right to worry about losing her husband – she was on the way to losing herself. It was the summer of 2004. She was 62 years old and, two years later, would be diagnosed with dementia.

Suchet is an experienced television journalist but writing about his own "news" must be tougher than anything he has ever had to broadcast. If dementia is about forgetting, this book has grown out of the need to remember. The style is conversational, bright and grimly compelling. And the memoir is an act of loving resistance.

His publisher suggested he write the book as a "love story" and this was a canny idea: love leavens misery and secures a small triumph – a refusal to allow dementia to have the last word or to erase a happy marriage. Romantic reminiscences (honeymoons, anniversaries, holidays in a beloved house in France) are intercut with a desolate present.

Bonnie presides over the writing of Suchet's memoir – his clueless muse, pacing the long corridor of their Baker Street flat or folding loo paper into neat piles, as if trying to bring order to a mind in tatters.

Most people are reluctant to think about dementia. But this is why it matters that books such as Suchet's are written and read. He discusses here what he might find hard to share in conversation (incontinence is only one example). He educates readers by describing the destructiveness of what has happened to his wife (although her condition is less aggressive than the norm). And he helps us to see the colossal strain on the carers of dementia sufferers.

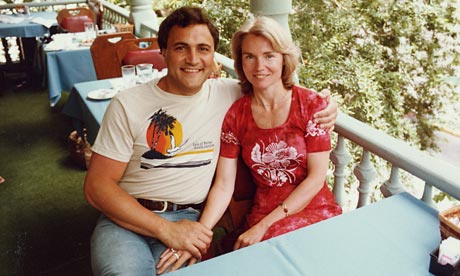

What is likable about the memoir is Suchet's lack of a stiff upper lip. He writes about love in the tone of a schoolboy, trying to make sense of an overwhelming crush. You might say he protests too much in his worship of his "east coast blonde" were it not obvious that his pride in his wife and admiration of her beauty – not to mention his appreciation of her sherry trifle – are so genuine. He writes of his frequent tears and how it feels to mourn someone who is alive and of his furious remorse whenever he loses his temper with her.

He is honest about unjust feelings that naturally assail him: "I resent her for what is happening to her," he explains.

Eventually – after much heart searching – Bonnie is moved into a home. And Suchet receives, at one point, the surreal consolation of a text message from one of the nurses telling him Bonnie is "dancing the hokey cokey with residents in Assisted Living and Reminiscence" (who thinks up these ward names?).

Meanwhile, he is embarked on something that will require fancy footwork of a different kind: he has become honorary president of Dementia UK and a passionate advocate for Admiral Nurses, who help the carers of dementia sufferers. He salutes his own Admiral nurse, Ian Weatherhead, saying simply that he "saved my life".

For all its heart, there is one thing Suchet's memoir lacks: any attempt to describe what is happening inside Bonnie's head. He has become incurious and defeated about science. "No one knows anything," he says.

Andrea Gillies's approach, in Keeper, is the opposite. Her outstanding memoir about looking after her demented mother-in-law has earned two awards in the last six months – the Wellcome and George Orwell prizes.

Gillies refuses to give up on trying to understand. She hikes across the blighted landscape of the Alzheimer's brain, trying to make neurological sense of it. She considers whether our personalities are more than biology – and even cautiously addresses the soul. Her destination is uncertain but her journey necessary.

The author has tremendous literary sensibility, nimble comic gifts and an over-developed capacity for self-criticism. In retrospect, she recognises the doomed absurdity of moving her extended family to a remote Scottish peninsula in pursuit of a Wordsworthian sublime (dependent on solitude) while attempting to care for Nancy – her violently dependent mother-in-law – and Morris, her depressed father-in-law. She also attempts to run a B&B. "She's quite a character, isn't she?" observes an Australian guest as Nancy streaks through the house naked except for a pair of over-large lilac briefs.

Gillies slogs heroically on: she serves tea and cake (as a "sedative") to her challenging in-laws. She battles to improve their lives long after uncomplicated sympathy has run out and she has fallen into depression (inevitably, the battle is sometimes with her charges). Like Bonnie, Nancy is eventually moved into a home – and is calmer there. Suchet and Gillies have each recognised the point at which they had to let go. Is there any comfort here? Only that both writers confirm the truth of Philip Larkin's line about death: "What will survive of us is love." It applies to dementia, too.