In the early morning, families spread rugs, plastic bags or even cardboard in order to sit on the pavement. As they gather to prepare breakfast on portable gas stoves, the smell of fresh barbari and lavash bread fills the air and tomatoes sizzle in the pan for omelettes.

Behind them is the tall, grey outline of the hospital, merging on bad days into the Tehran smog. These are fathers, wives and mothers from the provinces who have brought their loved ones here in search of a cure.

And with fresh barbari and lavash, they make it through the day. Warm bread helps keep patients, families and nurses afloat. In the dialysis centre, Mrs Fakoori is taking her turn to bring fresh bread for the entire ward. She is here with her 16-year-old daughter, Azadeh, who is almost blind in both eyes with diabetes, and Mrs Fakoori sits by her side, knitting shawls and sweaters as her daughter undergoes dialysis.

In many wards, the families of patients have an informal rota for buying the bread. Every patient looks forward to nine o’clock when it usually arrives.

But behind the smell of toasted wheat and sesame seeds, and the sweetness of the sugary tea served with the bread, are the realities of dozens of people who are seriously and sometimes terminally ill.

Qassem is a 10-year-old boy with large, curious brown eyes and a rare blood condition. He has come to the hospital with his 23-year-old brother from Qeshm Island, 1400km away in the Persian Gulf. Qassem lost both his parents before the age of three and his brother serves as his guardian. Full of energy while holding his brother’s hand, Qassem knows his test results better than the doctors and quickly corrects them if they utter a wrong digit.

Mr Nazari is 75 and comes to the hospital with his apartment caretaker. He has diabetes and two failed kidneys, but he insists he will live to 124: “110, but add 14 years for the 12 Imams, the prophet and his daughter.”

Farzaneh Khanom, the daughter of Mrs Shayeshteh, sits in a corner and complains to Miss Elahi, the youngest nurse, about her mother’s constant nagging.

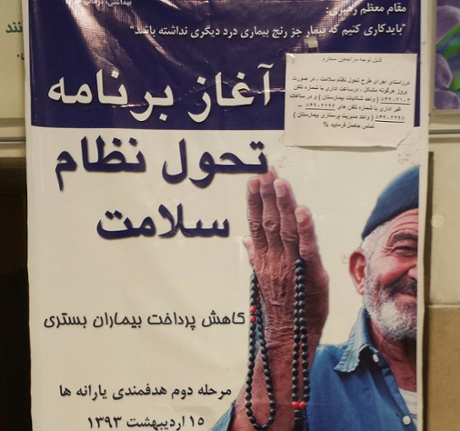

In the past six months, the number of patients at the hospital has doubled, and in some departments tripled, as the government’s new health scheme – the president called it “Rouhani-Care” on his Twitter feed – has been introduced.

“From all across Iran, every last person with some odd pain they never looked into, has now decided to have themselves checked,” one nurse tells me half with laughter, half with annoyance.

Under Tarh-e Salaamat (health plan), up to 90% of patients’ medical bills at public hospitals are paid for, more than ever before. It also covers additional costs outside the standard public health insurance that government employees have long been eligible for. It makes extra provision for remote areas and for people suffering from rare diseases.The first phase was rolled out in April 2014 and the second in September.

To benefit from Tarh-e Salaamat, patients must be hospitalised - that is, they must be on a hospital bed. The plan does not yet cover sarepayi, out-patient treatment (where they do not stay overnight), although the health ministry has announced that this too will be included in consecutive phases.

Anyone covered by public insurance can apply for their Salaamat card by going to Sazmaneh Tamin-e Ejtemai’e (the social security organisation), which also issues the standard public insurance. Where an individual is not covered by some form of public insurance, they can apply with their national ID card to the welfare organisation, which is run by the labour ministry, to secure their card. There is a desk in the hospital lobby that assists people with such questions, and the man behind the counter gives me this information.

On 12 January, in a ceremony celebrating the new health policy, President Rouhani said: “In my trip to the United Nations, I was asked even by heads of some European states how Iran had managed to establish a health plan.” He added that 8 million people had by then received their new health cards.

Health has been a focus of the Rouhani presidency, with his minister, Hassan Hashemi travelling across Iran to publicise the scheme and assess how the new policies are affecting remote, impoverished areas.

Tarh-e Salaamat not only covers costs but reduces strain on the patients’ relatives. Before the plan, any drug or tool necessary for hospital procedures had to be purchased by the patient, whose family would run around finding them: now the hospital covers everything. During a recent heart procedure for my father, we thought we had to find 3m tomans [£667, $1000] for an incision tool. Not only did the hospital pay, it provided the tool and so saved the trouble of finding one.

A senior policy consultant with the health ministry tells me Dr Reza Malekzadeh, head of research at the ministry (a gastroenterologist, and a health minister under the earlier administration of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani) is the brains behind the plan. “He’s always had an interest in public health and when the ministry finally received the 30% budget it had been promised years ago, they put it in action,” he said.

The 30% in question was a percentage of resources to be re-allocated from energy subsidies, including fuel, to the health ministry under a bill introduced in 2010 to reform welfare spending. However, in the Ahmadinejad years, it was instead turned into cash handouts or spent in projects such as the housing plan, Maskan-e Mehr, to supply affordable homes.

The consultant continues: “A plan like this needs consistent cash flow, and with oil prices as low as they are, it waits to be seen if it can be continued in the long run.” The Iranian media has reported 800bn tomans [£177m, $266m] as to what the scheme has added to the health budget for the current fiscal year, ending in March.

While government spending is under pressure because of diminishing revenue due to falling oil prices and lower crude exports due to sanctions, there are people from all over Iran at Tehran’s public hospital taking advantage of the new health provision. Children are among those from across the country seeking treatment.

Saturdays and Mondays are children’s days at the cancer centre when kids are brought in for weekly chemo injections and biopsies. The ward takes on a different life - more curious, livelier, but tragic.

“God loves you, you will get better,” says an aunt to Erfan, an eight-year-old boy with leukaemia who is crying loudly because he doesn’t want his chemo injection. “God doesn’t care, and I will die,” he snaps back, and continues sobbing.

The plan has especially filled in much needed gaps in the lives of the terminally ill. To use the public health system in Iran is a full-time job chasing signatures, waiting in lines, begging for approvals, and then starting all over again because someone signed a paper with the wrong date.

Although much of this work is still ours, it has reduced in load (and price) considerably in the past few months. “Patients leave the hospital satisfied, that was the aim of the plan and that is the result of the plan,” a head nurse tells me. And that has been our experience. The policy consultant echoes her: “Above all else, the aim was the satisfaction of the patient.”

Not all doctors agree. “Well-known doctors are refusing to perform surgeries, or assigning their students to do it,” a top surgeon at one of Tehran’s leading private hospitals tells me. “This will not end well. A functional health system needs cooperative doctors.”

Under the new plan, patients can more easily file complaints against doctors who charge more than standard premiums. This has been the health ministry’s effort to cap what doctors can charge for visits and surgeries, and has caused uproar, the doctor tells me, who insists the set amounts are not “realistic”.

Public hospitals in Iran are administered by public universities, and doctors within faculties of medicine also serve as physicians at the hospital. In recent years, it has become more and more common for these doctors to spend most of their day at a private hospital or clinic, causing some to question their commitment to their patients at public hospitals. The doctors’ prestige comes from the university, their pay cheque from their private practice. That is precisely what the health ministry has tried to address, with little success so far in overcoming doctors’ opposition and in some cases lack of co-operation.

The nurses are another dimension, little spoken of. More affordable care has increased demand. “It’s not even like we’re human,” one nurse tells me. “We’re robots, that’s what they think. The patients are receiving more thorough care, but at twice the number we had before we’re the only ones left to respond.”

I ask her if they have received new staff, extra pay, or the chance to give feedback. “Yup, our last pay cheque was four days late,” she snaps, “that’s what they did for us. Of course, when the plan was launched, we each found 230,000 tomans [£51, $77] in our accounts. A one-off gift. It was more like a diss. I wish they hadn’t done it. I can’t buy my son clothes with that money, what am I supposed to do with it?”

A head nurse at the nephrology centre at one of Tehran’s leading public hospitals tells me that they have repeatedly told the hospital board that they cannot sustain this level of work. “The least they can do is increase our pay, but they always say there is a section that needs maintenance or repair, that there is no money left.” She goes to add: “it’s a good plan, but as always, they build with no solid infrastructure in place, they just figure the staff will take the extra pressure.”

All the departments I check have no empty beds and long waiting lists. One nurse says: “We were always working overtime, but before, we occasionally had weeks where a few beds were empty - not anymore. We don’t have a moment of quiet.”

“We inject the chemo drugs, so we’re inhaling odd chemicals all day,” she continues. “Not only am I working crushing hours, I’m sure our lives are put in jeopardy. Who knows of the consequences of dealing with these drugs day and day out?”

Another nurse reiterates the previous ones, but she’s had a son in the hospital recently for a complicated heart procedure. She is the only nurse I speak to who has had the experience of both working and needing care since the plan was launched. “It is extra pressure on us, but my son had an operation that would have cost us millions of tomans. And we paid almost nothing. We didn’t have to run around the city for his prescriptions. It was such a relief. He’s home and feeling much better now, I’m grateful even though I’m exhausted.”

Along with the nurses, another group of people are instrumental in keeping the public hospital system afloat: the khadameh. The service men and women in theory wash floors and make beds, but many take on crucial roles organising patients, giving them extra care or providing them with services the hospital would otherwise not provide.

When Dr Mehraboon, the ward’s janitor, started taking care of my father at nights, doctors had said he would need three additional operations. Dr Mehraboon cared for him hour by hour, in a way the hospital never did, and revived his health. That is when we gave him the prefix ‘Dr’. And modified his name, Mehran, to Mehraboon (kind).

I ask a nurse with deep circles under her eyes and a cup of tea in hand, why she is here anyway, and if she would move to a private hospital if the opportunity came. She ponders my question for a minute. “I am here for two reasons. First, our head nurse who I’ve learned so much from, and who is the kind of boss that’s rare to come by, anywhere.”

She swallows and continues: “But also for the patients. I know this may sound strange, but I have learned so much from them. I have learned patience, I have learned trust. These are people suffering from the worst diseases, yet they smile. Some survive when we are sure they will not. It’s a weird kind of place, the worst and the best of the world in a few dingy hallways.”

Our father has been here, on and off, as a cancer patient for almost a year now. “It’s a gateway between heaven and hell,” my brother and I joke, in our hearts unsure what awaits any of us.

Some names have been changed