An artist whose wife lost three children during the early stages of pregnancy is raising awareness about the impact of miscarriage on men and that their grief is often ignored.

His latest exhibition, Labour of Love, is a celebration of the lives the family would have led had those children been born, and includes a 75ft scroll painting depicting them enjoying everyday activities such as playing in the park.

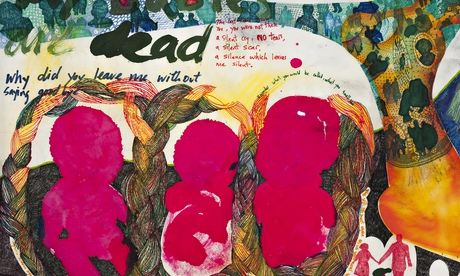

Andrew Foster, an award-winning illustrator, said he embarked on the artwork Pain Will Not Have the Last Word as a way of expressing his loss, and aims to challenge the perception that miscarriage “only happens to women”.

The exhibition, which closes on Tuesday at the Camden Image Gallery in north London, also features inflatable sculptures symbolising his emotions towards his unborn children. He says it is neither sentimental nor depressing, but joyous and thought-provoking.

The 46-year-old, who trained at the Central Saint Martins art school and is the father of two children – daughter Bonnie, 10, and son Frankie, 14 – said: “Both men and women will be moved by the imagery that celebrates the everyday experiences of fatherhood. There’s a need for it to be recognised that men grieve too. In our case, the miscarriages were all very early on – around six to eight weeks – and we thought, ‘We can’t keep doing this. We can’t keep putting ourselves through this loss.’

“We [Foster and his wife, Sophie] both recognise the three lives we lost are still part of our family while feeling very blessed that we have two beautiful and healthy kids who we adore and cherish.”

His plea for men to receive more support is backed by the Miscarriage Association, which has collaborated with him on the exhibition. About one in five pregnancies ends in miscarriage, and the charity is calling for an end to the isolation and feelings of being ignored that partners experience when their wives or girlfriends lose a baby.

A survey for the association’s awareness campaign, Partners Too, has revealed that 46% of those interviewed did not share their feelings for fear of saying the wrong thing or causing their wife or girlfriend further distress. By keeping their emotions hidden, men – and women – are at risk of their work being affected, and may even suffer mental health problems and relationship difficulties.

Foster, who has done work for London Fashion Week, the South Bank Centre and Liberty, said he had struggled with how to react after his wife’s miscarriages in 2010 and 2011.

“We never assumed anything would go wrong. Your head starts to go into overdrive and you start to make plans,” he said. “I didn’t know what to do or say after our miscarriages; I was just numb, devastated. I was surprised how little people asked me how I felt at the time, yet they say, ‘How’s your wife?’ The assumption was that the pain was only going on with her, not with me, and I felt very vulnerable as a man talking about a ‘woman’s’ issue. It’s amazed me that people have since said, ‘Of course it’s a male issue – take ownership’.”

It has been through art that Foster has been able to come to terms gradually with his loss, along with taking part in running events including the 2015 London Marathon.

He has also discovered that miscarriage is an all too common experience for others, including his parents. “My work has given others a licence to look at themselves, including my own father, who revealed that my mother had two miscarriages – they would have been my siblings,” he said. “Everyone knows someone, and you never forget. Of course, the loss of a baby is different for a man – it’s the woman who is carrying the baby. But it’s not a lesser one for a man. People say, ‘It’s good to talk’ and I’m fairly open, but I just felt this void and, if I was struggling to find words, then men who are ‘manly’ must find it even harder and isolating.

“That’s why it’s really important what the Miscarriage Association is doing to raise awareness. Sometimes it’s not about saying anything to you, but about a hug or just ‘Are you all right?’ My brother is a priest and he’s one of the few people who talked openly – he said, ‘You’ve had a massive loss.’ For me it made more sense to rationalise my feelings on paper.”

Ruth Bender Atik, national director of the Miscarriage Association, said that a macho culture was partly to blame for a man’s grief being sidelined: “We have a culture that says men should be strong, silent and supportive. We have partners who say, ‘I thought it would make things worse’, yet women complain that their partner won’t talk about the miscarriage, that they appear not to care. This puts a strain on the relationship.

“And people find out so early now that they are pregnant, which is both a blessing and a curse, given how common miscarriage is. We don’t assume that every man is going to feel devastated, but partners do get a raw deal and this needs to change.”