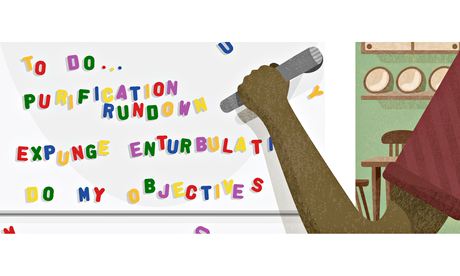

One of the strange things about Scientologists – and yes, I’m aware this sentence could end in several thousand legitimate ways – is their use of language. Recently, an interview in a Scientology magazine with the actor Laura Prepon was leaked online, and arguably it didn’t matter much, since it was impossible to understand. Prepon spoke of undertaking the “purification rundown”, eliminating “mis-emotions” by “doing my objectives”, and explained how much easier life becomes “when you really cognate that you are a Thetan”. Other Scientologists talk of “enturbulation” and “alter-isness”, “randomity” and “out ethics”, almost as if their entire religion were dreamed up (cognated?) by a pulp sci-fi author pulling everyone’s leg.

A private language helps groups like Scientology maintain control over followers; when no one on the outside knows what you’re talking about, there’s a strong incentive to communicate only with insiders. (For another sinister outfit that uses specialist language to preserve the power of a select priesthood, see academia.) But Scientologese isn’t simply jargon. It’s striking, specifically, for its reliance on made-up nouns. “Nounism”‚ as the social scientist Jeremy Sherman puts it, echoing Wittgenstein, is a way of “declaring things solid”. Nouns are the language of certainty, of things that can be grasped and dealt with. It’s easy to see how this might appeal to Scientology’s customer base, people adrift and desperate for firm ground. How reassuring to think that the cause of your woes isn’t human relationships, with all their messy unpredictability, but rather a straightforward case of enturbulation, plus a couple of mis-emotions, all easily expunged by means of a rundown!

You might never set foot in a Scientology centre, but it doesn’t mean you’re immune from nounism. We all do it, and it distorts how we see the world, bestowing on certain things an added reality they don’t deserve. (This is “reification”, in the lingo.) In his book Learn To Write Badly, Michael Billig shows how nounism makes things seem fixed, inevitable, beyond human control. “Globalisation” sounds like a force we’d better learn to live with, rather than the aggregate of countless human decisions; “depression” sounds like a stodgy blockage of dark stuff, not a collection of ways of seeing and relating to the world. Similarly, many commentators on the left seem to think “privilege” is a thing some people have, like acne or curly hair, rather than a description of the relationship between two or more individuals. And nounism lets us get away with lazy explanations like “religion causes terrorism.” Can a mere set of ideas – religion – really have magical causal powers, independent of humans? Nouns switch the focus from people to things, processes to static situations, hope to resignation.

We journalists must shoulder some blame, since nouns, especially short ones, have long been a great way to cram information into limited headline space. (If the mother of a sick child persuades the NHS to fund an experimental operation, you’re sure to read in your local paper of “Mum’s op bid joy for tot, 2”.) It’s not that nouns are bad, exactly. But there’s wisdom in the fridge-magnet cliche that life is a verb. Any form of language that fixes things will inevitably fail to capture the way life is a matter of ceaseless uncertainty and change. It’s all pretty enturbulating.

oliver.burkeman@theguardian.com