My mum can remember me having very sweaty feet even as a baby, but it wasn’t until I turned 26 that I discovered I had an actual medical condition that means that I sweat excessively. In school I drenched exercise books with my palms and I was so embarrassed about my constant underarm patches that I would always wear a blazer, even on sunny days. Eventually my mum sensed something was wrong and took me to see a couple of doctors who both said I would grow out of it. But I didn’t; I spent most of my time at school keeping myself to myself.

I had no words for my condition until 19 years ago, when I saw a documentary on TV about a girl who had a condition called hyperhidrosis. Like me, she couldn’t turn doorknobs or open jars as she had no grip. She was having an operation called an ETS (endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy), where they burn the nerve endings in your armpits and back. I went straight to my GP and asked for the same thing.

The doctor explained that ETS is keyhole surgery and that burning the nerve endings means that there is no way to reverse the process. (Now they only “clamp” the nerve endings, so you have the option of “unclamping” them in the future).

Several months later I was booked in for a two-hour operation to stop my hands from sweating. I was excited: I thought it was a miracle cure. They made a small incision under each armpit and partially collapsed the lungs to reach the nerve endings, before reinflating the lungs. It seemed to have gone well as I was taken to a recovery room. But all of a sudden I was rushed back in to surgery – something had caused one of my lungs to collapse. When I came round the second time I had a chest drain attached to me. I felt absolutely horrific; it took me over a week to recover. However, to this day, my palms haven’t sweated at all; I no longer get pangs of anxiety when I have to shake someone’s hand.

Unfortunately, the issue with ETS is that for most people it just displaces which orifice you sweat from. I knew there was a chance this would happen. While my palms remain dry, my whole torso sweats – I can soak a shirt in minutes. I have also developed gustatory sweating, which means I can be affected by certain foods. Some acidic, sour or bitter foods, like rhubarb crumble or lemon cheesecake, have only to be placed on the table to make me break into a cold sweat.

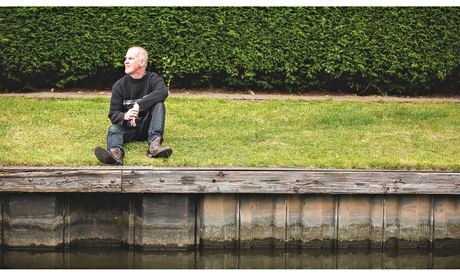

I used to be like a lot of sufferers and hide my condition, but now I’ll discuss it with a stranger if the opportunity arises, to help more people understand it. When I’m working in an office I always wear a jacket. People say things like “Aren’t you hot?” but it’s better than them asking me, “Why is your back so wet?” Now I work as a night controller in the construction industry, which means cooler weather and fewer people.

People usually assume that if you have it, you also smell; that’s not the case. People often say: “Oh I sweat a lot, too.” Nothing could be more annoying for a sufferer to hear. When you have hyperhidrosis it is like having a tap you can’t turn off. It controls your whole life – where you go, what job you do and all your social interactions. I can see why so many sufferers end up with depression.

I became involved with a support group for British sufferers a few years ago and then decided to set up a Facebook page to make those with the condition feel less alone. The group was slow to start, as people didn’t want to publicly acknowledge that they had it. However, over the years it has become more and more active; it is now a lively global forum with nearly 2,000 members.

I am 45 now, and I’ve got used to adapting. I hold on to the belief that one day there will be a cure, and hope that I have managed to help other sufferers. Sadly, my eldest son, aged 19, is beginning to show signs of having inherited it, which makes me feel guilty. But I can help him through it, passing on the coping mechanisms I have learned. I hope hyperhidrosis won’t affect his life as much as it has mine.

• As told to Kate Samuelson.

Do you have an experience to share? Email experience@theguardian.com