Six or seven months before he died, I met Harold Pinter and asked him how he was. This was the result of a mishearing on my part. It was at a dinner in a restaurant for the writer Simon Gray – his friend and my friend, too, though theirs was by far the closer and older friendship. He came into the room and leant on his stick at the edge of the crowd. He looked frail: his carpet slippers and his little naval cap suggested a body weakened by illness and tenderised by therapies: radio, chemo and possibly physio. I went over to greet him – I was one of the hosts — and I thought I heard him say, "How are you?"

"Fine thanks," I said. "How are you?"

"I didn't ask you that question," Pinter said. "I never ask people that question. It's a bloody stupid question."

"Oh," I said, and "Um."

I knew how inflammable he could be. When Pinter died, Michael Billington in this newspaper mentioned that he had "a reputation for being short-tempered". Yes, and the Pope sometimes remembers to say his prayers. Gray often witnessed the full paroxysm. "When he becomes angry, the eyes become milky, the voice a brutal weapon that is virtually without content," Gray wrote in his memoirs. "What I mean is that he speaks violently, really violently. His voice is like a fist driving into you, but he uses almost no words, three or four at most – 'shit', 'fuck' and 'I' are the ones you hear – [the rest are] dark and ugly sounds incomprehensible because they are not intended to be comprehended except as dark and ugly sounds, and full of eloquence therefore."

I submitted myself to the storm. "What an insufferably silly question," Pinter continued, cruelly imitating my 'How are you?' like a bleating sheep. "Sometimes I come into my office in the morning and I hear my secretary on the phone saying, 'Fine, thank you', and I know the stupid question she's just been asked!" His timbre was turning from sheep to the more familiar Alsatian. "Why do people say it? Why? Such a pointless and ignorant question."

Eventually a bystander – out of gratitude I name him as the novelist Howard Jacobson – intervened. "Oh, come on Harold, it's just a little social ointment, helps make the wheels go round," Jacobson said, or words to that effect. "Really? Do you think so?" Pinter barked. "Well, I don't. Fucking stupid question. I never ask it and I don't expect people to ask it of me."

A chair was found. The playwright sat down. Gray came up to me and whispered mischievously, "And how are you, dare I ask?" Then we all went in to dinner and toasted Simon and his new book. I began to forget my humiliation until, over the sweet, I overheard Pinter growling to the woman who sat between us, "How are you? How are you? Don't you think that's a bloody silly question?" So it was not to be forgotten. Instead, I made a story out of it, preserved it as an anecdote to illustrate Pinter's sudden and inexplicable rages. (A mild example, actually.)

And now I think he was right; or rather I now think I understand what so maddened him. Pinter had endured seven years of serious illness by the time of that encounter in 2008 – cancer of the oesophagus followed by cancer of the liver – which means he must have been greeted in this way thousands of times by people who knew he was ill, which was almost everyone he came across because his illness was well-known. Plenty of time, therefore, to consider it as a personal question with replies that might range from the outright lie through the formal to the truthful – from the brisk "Never felt better" through the "Fine – and you?" to the several sentences that might begin to describe how he actually felt: honest details that his greeter might not have intended to provoke or relished hearing. As the owner of an illness – nothing remotely as serious as Pinter's and now quiescent – I've sometimes given in to the truthful option and treated my questioner to the specifics of steroid dosages and joint pains; and then felt ashamed because I seemed so self-pitying to a person who was using "How are you?" only as a three-word form of hello.

The trick, of course, is to divine the intention from the emphasis. "How are you?" usually (though not invariably) means the speaker has some interest in the answer, an interest that can either be embarrassing, because you don't want to be an object of public concern, or alarming, because you fear you must look half-dead, like the poor chap in Stanley Holloway's monologue My Word, You Do Look Queer whose gloom increases the more friends he meets: "How old are you now?/About 50, that's true/Your father died that age/Your mother did too." Safest in either case to reach for a bromide. "Much better, thank you." "Oh, up and down." "One day at a time, you know, one day at a time."

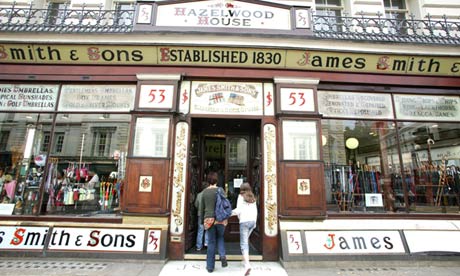

In this context, the sight of a stick doesn't help; it alerts people to the prospect of frailty. I never expected to have a stick. I hope I won't always need a stick, and even now I often leave home without a stick. Nevertheless, when I bought a stick, I decided to embrace stickness and went to the world's most famous stick, cane and umbrella shop, James Smith & Sons in New Oxford Street, which was founded in 1830 and whose clients have included prime ministers and viceroys of India. A very well-mannered though decisive young man asked what kind of stick I required. A crook or a derby? And in acacia, hickory, cherry, maple, ash? I chose an ash crook. He found one that seemed to me exactly the right length, but he decided it was too long. There is a formula: to get the right length, divide the user's height in two and then add half an inch, or measure from the wrist to the floor.

"I'll just have it cut for you sir." He bore it away to the workshops, like I imagine the shop assistant did in Evelyn Waugh's Scoop when he had William Boot's cleft stick cloven in the cleaving department. But the reduction was unsatisfactory. It never felt right to me – too short – and so I eventually got another stick, a derby this time, with a sprightly flat handle rather than a droopy curve, and at a length that disobeys all the wisdom Smith & Sons have acquired over nearly two centuries of stick production. I like it. Until you have a stick, you never realise how ubiquitous they are, with especial densities at certain times in certain places – a London bus, say, at 11am – when a derby in maple can stand out as rather special.

I can't remember what kind of stick Pinter had that night. It would be nice to think it was a whangee, the bendy bamboo leant on by Charlie Chaplin's tramp; or a silver-topped cane of the kind tapped by Fred Astaire; or a hollow "tippler" that you could pour a drink from during prohibition. All of these would have suited him, though the likelihood is that he was supported by an NHS standard-issue. Whatever the case, knowing what I know now, I wish I'd just said: "Good to see you, I like your stick."