American yoga practitioners are abuzz with a new controversy rocking their once boutique but now rapidly commercialising industry: magazine advertising and public yoga classes featuring unabashed nudity. The controversy pits seasoned yoga teachers and other spiritual purists, who abhor the growing trend, against a new generation of aggressive yoga "entrepreneurs", anxious to promote the ancient Hindu practice as America's premier "wellness" lifestyle – even if it means exploiting, as critics maintain, the female "beauty myth" and embracing a "sex-sells" marketing strategy.

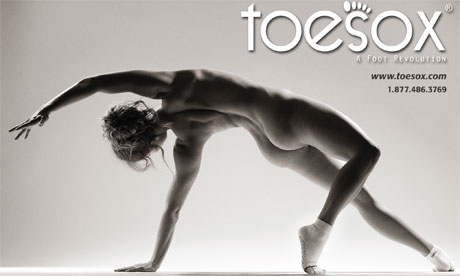

So far, the two sides have largely confined their debate to articles and blog postings in popular online yoga magazines, including the industry's trade publication, Yoga Journal, where nude and semi-nude ads featuring a prominent Los Angeles yoga teacher, Kathryn Budig, first started appearing last summer. Budig posed provocatively in ads for the clothing manufacturer ToeSox, which prompted one of the magazine's original co-founders, Judith Hanson Lasater, to protest publicly, first in a letter to the editor, and more recently, in interviews.

For yoga purists, it's bad enough that yoga is no longer the quiet, esoteric practice of yore. Thanks to heavy marketing, and word-of-mouth advertising, it's now a bustling business worth $6bn a year and featuring a gallery of self-promoting yoga "celebrities" like Budig, and an endless array of high-priced yoga accessories, including sticky mats, CD-roms, home videos and pricey yoga retreats and vacations in exotic Third World getaways.

Until now, many have tolerated, and even celebrated, yoga's commercialisation as a way of promoting its popularity, even if it means "dumbing down" the practice or heavily tailoring it to the traditional fitness market to further expand its appeal. According to Yoga Journal, some 18 million Americans – about 1 in 10 adults – were practising some form of yoga in 2006, though the numbers seem to have fallen off in recent years, even as the revenues generated by the industry continue to grow.

But something seems to have cracked inside the souls of long-time yoga enthusiasts when Budig agreed to be photographed wearing only her ToeSox. In one of the photographs in the series of ads, she's in a difficult Ashtanga yoga pose, known as "firefly", and her expresson is serious, but the effect is oddly disconcerting. Is it "art", as some of its ardent proponents, including Budig and ToeSox executives maintain, or is it merely the latest twist in a long history of sexual and commercial exploitation?

The debate over nude advertising and health & fitness is hardly a new one. Four decades ago, Sports Illustrated caused an enormous stir when its cover featured a topless woman jogging on the beach. Critics, including me – yes, at the tender age of 10, I wrote a letter to the editor that was published – suggested, naively perhaps, that topless women simply don't belong on the cover of a serious sports magazine. Others saw it as a celebration of the human body, and of the joyful exuberance that one experiences through jogging and other forms of exercise.

Clearly, our mores have changed – or have they? In 1999, women's soccer player Brandi Chastain caused an enormous controversy when she spontaneously stripped off her jersey after kicking the goal that ensured her team's victory. And Chastain didn't expose her body – just her sports bra.

Male soccer players often doff their shirts, but, of course, men exposing their chests in public is commonplace. Amazingly, people to this day debate whether Chastain crossed an imaginary line of female "propriety".

But is yoga somehow different? Perhaps. For one thing, it's not meant to be a sports activity, and the persons exposing themselves, while celebrities of sorts, claim to be spiritual models, and some, like Budig, have direct contact with us, their students. According to Lasater:

"[A]ll this sexualisation of yoga through props and advertising [affects] the environment of yoga classes in ways that do not honour the boundary between teacher and student. I want to help create a safe space for yoga to be taught. In the US, we pay people the most money who can distract us the best: actors, personalities and sports figures. Entertainment is all about distraction. The use of naked bodies to sell yoga products is about using distraction to sell introspection."

Others are equally worried that selling yoga with fit, trim bodies – almost all of them young and white – imposes the same harsh psychological burden on women that traditional fashion and beauty advertising does. Even more, perhaps, because women with serious psychological or physical health issues – such as obesity, as well as anorexia and bulimia – are drawn to yoga to affirm themselves, regardless of their "looks" or how they might feel about their bodies.

Budig, however, disagrees, and so do many yogis, especially – surprisingly, perhaps – many women. They see her as a courageous role model for self-expression, who is simply saying, I love my body, and what I can do it with it, and you should, too. But it is also clear that Budig is using the controversy to promote her own yoga business, and to enhance her own celebrity. Equally, ToeSox appears to be exploiting her yoga connection – and body – to appeal to a key consumer niche for its product.

The appearance of Budig's ads – and others similarly controversial, including one titled "Say No to Cameltoe", parallels the sudden emergence and rapid proliferation of "Naked Yoga", yoga classes conducted entirely in the nude. Its founder, Aaron Star, says many people, especially in cities like New York and Los Angeles, don't have ways to express closeness and intimacy without having sex, and that his practice affords that. But Star's also heavily promoting Naked Yoga videos that feature full nudity and bear a strong resemblance to soft-core pornography. He's even provocatively entitled one of his new videos apparently designed for the yoga beginner, "Hot Nude Yoga Virgin".

But if so, why stop at nudity? It's conceivable that someone might try to create a business that exploits yoga's Tantric roots even further, promote studios where students can engage in erotic exchanges with their teachers? Actually, that already happens, but so far, no one's figured out how to make a buck off of it, without actually breaking the law on solicitation.

Does all this fuss over yoga and sex reflect the enduring strength of American puritanism and prudishness? Are critics merely jealous killjoys? Supporters of Budig and the new nudity trend in yoga certainly think so. But it's also true that yoga is one of the few industries of its size that exists with virtually no regulation – either from public authorities, or from within. Last summer, about the same time the nude trend emerged, New York and Virginia tried to impose state guidelines on yoga "teacher training" programmes – the programmes that are used to teach advanced students to become teachers themselves. But heavy lobbying by yoga associations in both states beat back those efforts, claiming yoga was a "spiritual" enterprise, much like a church, and should be "exempt" from all government interference.

A spiritual enterprise with revenues of $6bn a year? That's some pose.