In the US we've heard the refrain for two decades: early detection saves lives. But this week a federal advisory board decided that while that slogan wasn't false, in the case of breast cancer, it just wasn't true enough.

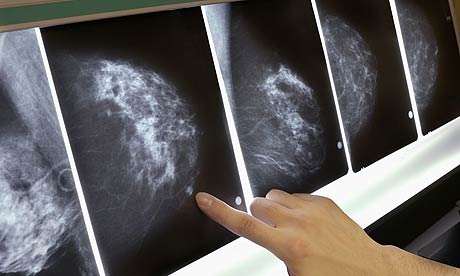

After years of pink ribbons and breast cancer marches and admonishments to examine our breasts, this week the US Preventative Services Task Force bucked conventional wisdom (and the American Cancer Society) claiming that the number of women saved by early detection through mammography was not enough to warrant the recommendations nearly every schoolchild can recite: a mammogram a year after age 40. Citing anxiety – real, as every woman who has waited for her mammogram results can attest – caused by false positives and unnecessary (and, yes, again anxiety provoking) biopsies, the federal agency announced that henceforth the guidelines would advise women to seek mammograms only after age 50, and only then every two years. In other words: the NHS model.

Women in America have long had one edge over their British counterparts – a recommendation that we be screened annually, a full decade before our friends in London and elsewhere, beginning at age 40, for breast cancer. American women, more likely to pick up their cancers early, have a 97% chance of survival five years post-detection. Our sisters across the pond? Only a 78% chance. Since 1990, the number of American women dying of breast cancer has dropped by 30%.

As Dr Angela Sie, director of imaging at the breast centre at Long Beach Memorial Hospital, told the Los Angeles Times, changing the rules "would be a huge step backwards for women's health in this country."

Certainly, my family is pleased these recommendations didn't exist twenty years ago. My mother, not to put too selfish a spin on it, was a beneficiary of the previous regime. Her first breast cancer, caught small – terrifying but manageable – at age 43. Her second – again picked up on a mammogram – at age 49. A double mastectomy and radiation, no picnic, as we Yanks like to say, to be sure, but she's still here, still calling me four times a day, still clomping after her dog at night, still bugging my dad in the morning. For this I am grateful we were insistent on mammography. But for this I worry for all those whose mothers and sisters and selves will no longer benefit.

The doctors of the task force – which, notably, contains not a single oncologist – have reassured the public that women in higher risk categories would be urged to have conversations with their doctors about whether their screening should start sooner. Said Dr Diana Petitti, deputy chair of the task force: that women should not be screened in their 40s…. We're saying there needs to be a discussion between women and their doctors."

The water is muddied. A phenomenally successful public service campaign scuttled. And for what? What is risk? Who are we shunting aside in the hopes of preserving calm over screening? Screen women in their 40s, according to the Annals of Internal Medicine, and you see a 16% mortality reduction – 6.1 deaths per 1,000 women are saved. Some 40,000 women die of breast cancer every year, and cancer is the leading cause of death of women in their 40s. (For the record, breast cancer is about 100 times less common among men.)

Consider that the Food and Drug Administration is considering banning raw oysters from the Gulf of Mexico to save the lives of 15 people who die each year from bacteria in contaminated oysters. The shellfish industry is up in arms. But for the families of those 15, treating those oysters or forgoing them is worth the federal effort.

Fifteen deaths from oysters. How many thousands from breast cancer? No wonder the Obama administration backed away from the panel recommendation. Beyond potentially complicating the already complicated end-game for health-care reform in the US Congress, who wants to tell a family that their mother wasn't statistically significant enough to save?