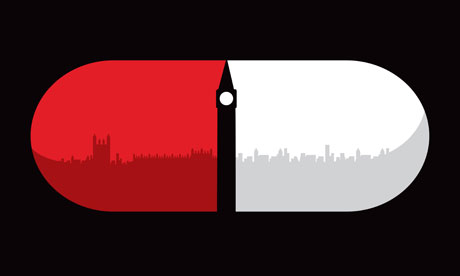

So a spoonful of sugar pills helps the waiting lists go down, or so your doctor probably believes. More than nine in 10 British GPs have quietly doled out placebos to patients and most seem to think there is nothing terribly unethical about it, according to a study published this week, which opens a rather fascinating can of worms.

Experience suggests that authority figures fobbing us off with empty promises is rarely a good idea. And yet rather awkwardly, placebos work, sometimes well enough that it seems ethically dubious to withhold them. If that's what it takes to reassure a patient, or help them heal themselves, is an unnecessary dose of antibiotics or handful of clinically worthless sugar pills really so wrong?

Nobody likes being lied to, obviously. Yet interestingly, sham treatments work even if the doctor doesn't lie: in one experiment, sufferers of irritable bowel syndrome were explicitly told that they were getting useless dummy pills, yet their symptoms still improved, perhaps because the doctors quite truthfully added that fake pills had sometimes been seen to work. Proof that a tablet is never just a tablet, but is hope sealed in a blister pack, all wrapped in the powerfully healing sense that someone takes you seriously – that your pain matters and that, by extension, so do you. And that resonates far beyond medicine.

Half a century later, the pain felt by Australian victims of forced adoption – unmarried mothers who were compelled, or tricked, into giving up their babies for adoption from the 1950s to 1970s – cannot possibly be undone by politicians. Warm words from a prime minister who wasn't even born at the time can surely have no real impact on their distress. And yet, to watch Julia Gillard apologising on the nation's behalf, as tears flowed freely among her audience, was to understand the effect that placebos can have in politics. To have your suffering finally acknowledged, to be made to feel that finally you matter and your emotions are worthy of respect, is not nothing – just as it was not nothing for a Conservative-led government here to embrace gay marriage.

They are everywhere in politics, these seemingly meaningless gestures that somehow count for more than the sum of their parts. We tend to be cynical about them, regarding them as cheap stunts, which some of them are – worse, some of them are expensive stunts. But, like placebos, they are not always useless, even if they do not work in conventional ways.

It is a cliche of criminal justice policy, for example, that bobbies on the beat do not reduce crime but merely create a comforting illusion of safety. But is illusion always a bad thing? When fear of crime is out of all proportion to recorded crime itself, fear has a palpable effect – keeping the elderly inside and isolated; encouraging parents to drive their children everywhere; driving people out of public spaces at night and thus paradoxically making those spaces less safe – so it follows that reducing fear has value, too. High-visibility patrols deployed in the aftermath of serious violence or terrorist attack are surely more for reassurance than anything else, but that doesn't make them worthless.

In economics, too, placebos have their uses. Chancellors talk glibly of restoring confidence as if it were a scientific process, a matter of getting the fiscal medicine right. Yet, in truth, much of it is bluff, managing the public mood as much as the money, promising to guarantee savers' deposits in the knowledge that the promise alone should prevent a bank run. Even a VAT cut shaving a few pennies off at the till may have a disproportionately feelgood effect, despite making little real difference to many consumers. If nothing else, small gestures ward off the sickening feeling that politicians have no cure for what ails us, that perhaps there isn't a cure.

We say that we would like politicians to be more honest, to admit to not knowing the answers, but as the writer John O'Farrell pointed out after coming fourth in the Eastleigh byelection recently, we tend not to vote accordingly. Perhaps we should be more honest about how much reality we can actually bear.

The comfort of a placebo, of course, comes at a price, and that's the erosion of trust. Even well-intentioned paternalistic deceit undermines the moral authority of those peddling it: it's hard for doctors to criticise the whackier fringes of alternative medicine if they're dabbling in quackery themselves. And a white lie is still a lie, a failure of nerve, a missed opportunity to explain a hard economic or clinical reality. Yet what if a placebo could make the patient better where an explanation would not?

Perhaps the only sensible conclusion is that placebos should only ever be used in the patient's interest, never lazily in the prescriber's. This means no doling out unnecessary antibiotics simply to keep fussy parents happy, because it risks spreading antibiotic resistance; no spraying pre-election tax cuts around to create the illusion of generosity, if it means a savage reckoning later. But we should not underestimate, either, the power of words and the importance of acknowledging human fear and pain. There is more than one way to do no harm.